You know that meme about how a single Chili Heatwave Dorito would kill a Victorian child? Well, we can only imagine Rayon Vert would have an equally strong effect on even the hardiest Victorian hiker. Raiding the spice-rack for serious flavour, the Italian brand pulls in references from some of the finest sub-cultural realms to create the kind of rich and potent stew rarely tasted in the outdoor world.

Their website is like plugging an ethernet cable into the back of your neck and reliving the glory days of the dial-up era. Their expertly illustrated logos look like they were ripped straight off the box of a fantasy board game. And they spend as much time making zines as they do clothes.

It’s not style over substance either—and their ultralight backpacks and lightweight technical gear is crammed with the kind of ingenious idiosyncratic details that only come from serious time spent in the mountains.

Founders Yuri and Andrea were recently over in Manchester to visit the new Outsiders shop and take a stroll down the A6, so while they were in town we caught ‘em down by the banks of the Irwell to talk about backpacks, their open source attitude to outdoor clothing and the importance of not being boring....

Sam: Rayon Vert started out back in 2017? What was going on back then?

Yuri: In 2017 we started to have this interest in ultralight backpacking—looking at it mainly on Reddit and YouTube. We came to it from the product first because we found these nerdy blogs of people that were sewing their own stuff using esoteric fabrics and we got fascinated by the deep analysis that they were putting into every detail. They were counting every gram, carefully thinking about where every stitch had to be made or which fabric was better than another one at a microscopic level.

We were like, “Oh, this is so fascinating. Where does this thing come from?” so we started geeking around it—we bought a few books and we started informing ourselves—and after a while, we started going to the mountains. This was in a period where it was a bit more difficult than nowadays, because the smartphones weren’t so smart. You’d go to a blog and people would say something like, “When there's a big rock, you have to turn and then you have to take the third trail and then you have to turn when there's that tree.” Every time we started a trail, we got lost or we finished in a different place because it was impossible to understand the descriptions. Everything was very complicated.

Sam: And did making things kind of go hand in hand with that? Was it a natural thing to try and make your own gear?

Andrea: When we started doing long hikes—these multiday unsupported hikes—there wasn’t really the hardware for that purpose at the time. So we started sewing our own by teaching ourselves how to do it. At the beginning, Rayon Vert wasn’t really a brand—we were sewing backpacks and sleeping bags, but there wasn’t the purpose of selling them.

Sam: That classic thing of, “I need this, so I’ll make it.”

Andrea: Yeah—because we couldn’t find it. It was a DIY thing, and then after a few years of developing the backpack, people kept asking about it, so we thought, “Okay, maybe we can sell it?” So that was when we actually started the brand with the logo and stuff. But that didn’t really change anything. The people asking us about the backpacks were having the same struggle as us, so the idea stayed the same. It was just a natural step—just following the same exact approach without questioning too much.

Sam: I like that DIY approach. Sometimes it’s easy to forget that you can make things for yourself when there’s already these huge companies out there.

Yuri: When we started—and I would say even today—the thing we were looking for wasn’t on the market. We wanted something that we could wear in the mountains that has a fit and a style that could match what we were wearing everyday. We come from a very street kind of background—really into music, graffiti, biking and punk. We wanted to bring that kind of aesthetic to our activities in the mountains. We tried to bring the graphics and aesthetic and the fit, and combine them with technical garments.

Sam: That makes sense. I know early on the idea of ‘open manufacturing’ was a big influence. Can you explain what that is?

Yuri: Open manufacturing is the idea that there can be a shared amount of production inside every city. It’s about having full control over the production chain and how the processes can be managed inside the community.

And we did many projects related to that—like our first collaboration with Slam Jam. The whole idea was about selling unfinished garments—we just sold the cut pieces of fabric and the people could then sew them. The whole idea was that people would have learned something by sewing them and developed a critical understanding of how a garment is made.

Sam: And they’ll respect them more because they’ve had a hand in making them—it’ll mean so much more.

Yuri: And even if they don't do it themselves and they bring it to a repair shop, they’re also supporting the social fabric of their neighborhood or their community. It's all about educating your public, so now they’ll know about which fabrics work for them, or how to make a stitch or if they need a pocket made in a certain way or not.

Even if right now we, as a brand, are a bit more industrialized compared to back then, there’s always the idea of giving to the customer a product that is maybe 95% finished, so the customer has to put the remaining bit there.

Sam: Like the Fubar pants that aren’t dyed?

Yuri: Yeah, exactly. In this specific case, we encouraged people to buy our trousers in the undyed version, which has several advantages—no water is wasted on industrial fabric dyeing, and virtually anyone can have trousers in a colour different from everyone else's through dyeing—which can be done in countless ways, some more sustainable than others.

Sam: That breaks down that barrier between maker and wearer a bit doesn’t it? It’s easy to be precious with things like clothes or bikes or cars or whatever, but you can actually get them and change them and cut them up and do whatever you want. That’s kind of liberating.

Yuri: One of the coolest things about bikes to me is the aftermarket and the fact that you can change parts to your bikes—but nowadays that’s way more difficult because the standards are always different and it's something that the market doesn't encourage. If you break something on a modern bike now, you probably have to change the whole bike, because in five years there’s probably not going to be the spare parts to replace it.

Sam: Things are very ‘precious’ and dainty now—it feels like you need an engineering degree before you can touch a modern road bike. You guys come from a different angle though—even your technical gear feels approachable and ‘moddable’.

Andrea; Yeah, if we were going to do a waterproof jacket, we know that it's going to be an active jacket, that has to resist water and still needs to be breathable and all that—but for a small brand like us, it's difficult to reach the kind of manufacturing that the big brands have, so we take the same idea and work in a different niche of technical clothing.

For example, we are exploring a lot with wool and organic fabrics. There are so many brands that do the advanced thing well, so why not have another take on things?

Yuri: There's always some other route that you can take or elaborate on.

Andrea: And as a user of functional clothes, you quickly understand what you really need—you quickly teach yourself what is marketing and what is function. And the idea of Rayon Vert is that we’re the user—we wanted to create things that we actually can use outside but without hiding behind certain marketing gimmicks.

Sam: You’re not just ticking the boxes—like, “We need 20 t-shirt designs and a full range of trousers to be ‘a real brand’.”

Andrea: That actually happened a bit in the beginning when we started to wholesale. When Outsiders got in touch, asking us if we sold to shops, it was totally out of the blue. We were like, “We’ll try!” We thought “Okay, so it's a store, maybe they need to fill those racks with multiple and redundant designs?”

But now we’ve reached our fifth collection, and we are now going in the opposite direction. We want to condense things and just have products that we believe in—like the Fubar pants. When we find a product that works, all we care about is continuing to produce it and improving it where necessary, whether that means changes to the fit, new solutions or a change of fabric. We believe that every product is evolving, and if it works, why change it? That’s more the direction we’re taking things now—we’re more aware that you don’t need as many things.

When we started looking at making backpacks years ago, we found this company that just made one backpack—that was it. They were just this small cottage company, and that’s what we’re more into now, this idea of having just a few things which work very well. Those cottage companies are a big reference point for us now.

Yuri: There’s something very fascinating about these companies which stay small and continue to produce it themselves—but outside of the outdoor world we also look at music labels, small skating brands and punk labels.

Andrea: Another thing is that now ‘the active’ has spread into a lot of different categories which communicate with each other. Years ago, if you had biking clothes, they were just for biking, the market was very sectorized. But now if you can have a t-shirt that works for biking, you can use it for trail running or hiking or whatever.

Sam: Everything has kind of blurred.

Yuri: Yeah—because after a while you understand that if you're outdoors, you can have a very specific modification to a garment for each sport, but in the end it's not that relevant.

Andrea: The big brands always speak to the top performance people—creating specific clothing for the athletes, but the reality is that the world is full of amateurs—and amateurs don't need those clothes.

Yuri: They just like the idea of performance clothes—but there can be other values. Clothing can be more ethical, or maybe it’s more functional for a longer period of time, or maybe it’s just cooler? There are many other aspects of a garment beyond just pure ‘performance’. Don’t get me wrong, we are always looking for the highest performance, but very often certain items of clothing end up being a bit of an end in themselves. I don’t really think there’s much difference between a technical shirt for running, one for mountain biking, or one for playing football, when the fabric dries quickly and has good properties in terms of weight and fit.

Sam: And the long distance hiking thing requires very different clothing to say, ‘lightweight race clothing’. You want something you can fix easily—things need to be kind of simple and humble to really last.

Andrea: Yeah—I remember back on the ultralight blogs people were talking about waterproof jackets, and they’d say, “You don’t need the expensive jacket, you need the jacket you buy at the gas station—that’s the best.”

Yuri: Honestly speaking, probably the best waterproof jacket is a plastic waterproof poncho that you can buy for a couple of Euros. It covers you, it covers your backpack and you have a lot of ventilation underneath.

Sam: And what’s cool about that is that it comes from user experience. Ideas that come from user experience and communities working things out are so much more valid than ideas that are just sold down from the top. Looking through your output, not just with your gear, but your amazing website and the zines you make, there’s a lot of character and flavour—how important is it to get that across?

Yuri: I think it's essential to not be boring and try to put as much input as possible into the brand—we’re like a big soup of ingredients. It's really a shame that every brand nowadays has the same logo, the same website with the same sans-serif font. It's such a shame in terms of what can be said and what can be done.

Andrea: To me it’s like the products can only speak until a certain point, but then you need other tools to express what you are doing and what you are. Like yesterday, Charlie from Outsiders showed us these running shoes that are made in the UK called Walsh—it’s interesting to see things like that have a story behind them.

Sam: Yeah—to look at them they might look strange, but then you learn that the founder was a guy who used to work at the brand that became Reebok, and they were designed by a fell runner specifically for steep and muddy British terrain, and they start to make sense.

Yuri: For us, what we like the most is to be as sincere as we can be. We as people are deeply in love with so many things—so we try to get that across with what we do. There are so many references that come from so many different worlds, and that’s because that’s what we like and that’s where we come from.

Sam: I loved that Blizzard Entertainment logo-rip you did. Do people pick up these references? Or do they go over peoples’ heads? And does it matter?

Yuri: I think both of those reactions are good. If they’re lost on people, that’s also something we really enjoy. You know—it’s like those movies that you see and when you arrive at the end you don’t understand what just happened—those are the movies that stay with me.

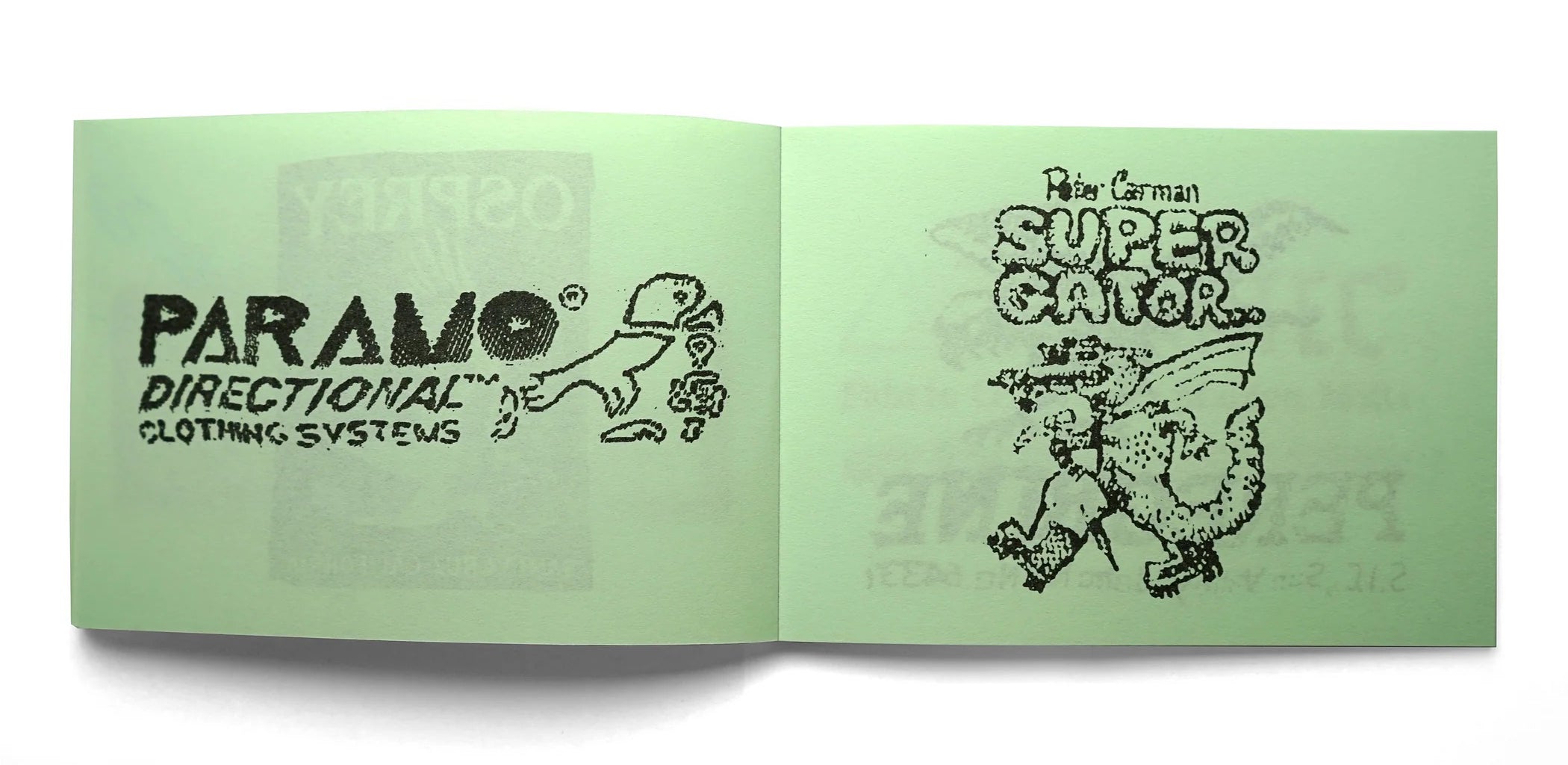

Sam: That zine you made of the old woven outdoor labels was a cool way of showing how much flavour those old brands had. How did that come about?

Andrea: That was made with Luca Lozano—a UK DJ. He does these zines which are these collections of different logos…

Sam: Oh yeah I’ve seen them—like old reggae label logos and stuff?

Andrea: Yeah, or early internet logos. He asked if we wanted to do something with him, so we started collecting all these woven labels. Nowadays graphics in the outdoors are really minimal, but back then these were a really loud way to speak about the outdoors. Even though they’re just these small woven labels, they would still fit in a lot of things.

Sam: Some of them are amazing. Even fairly middle-of-the-road brands in the 70s really went to town on their labels—it’d be the most normal flannel shirt ever, but then on the neck label there’s this intricate image of some grizzly guy in a canoe thrashing down a river or maybe catching a big trout. Changing subject slightly, can you tell me about the Wormholes glasses you make? There’s quite a lot going on with those.

Yuri: They come from the mind of this guy called Spencer who has this one man brand called Abicsi. He found this way to create 3D printed glasses with very high definition. He had this desire to create something on his own, and in the sunglasses world that’s very hard because it’s a monopoly.

Sam: I’ve heard that—one brand kind of owns everything doesn’t it?

Yuri: Yeah, and when a new brand arrives, they buy it. But with lots of trial and error he found this way to do sunglasses made of nylon. And since they're made of nylon, you can use many of the same techniques that you can use on garments to dye them—dying them in a bath.

He created his own machines to test them in many different ways, from how they break apart to how lights permeate the lenses. He texted us and said, “I think we share lots of common ideas and I would love to develop a product together.” And since then we’ve had this back and forth. We bought a 3D printer, he started sending us his first files with the prototypes, we tested them, we modified the shape and we sent them back… it was this beautiful exchange of his point of view and our point of view to create a pair of sunglasses that satisfied our needs.

And yeah, that's it. And still, nowadays, this is a product that is made in-house and it doesn't share the market rules.

Sam: I suppose the 3D printer is kind of an amazing tool for that ‘open manufacturing’ thing you were talking about before. It’s about ideas, and not the exclusive finished product.

Yuri: Of course. Most of the time the product is overrated—the product is just the end of a process that starts way before. In terms of why you buy one product instead of another one, there are so many factors, from marketing to storytelling, even just for a cotton t-shirt.

Sam: That open source mentality seems like a big theme for you—even on your website where you’ve got the hiking routes and maps. There’s a lot of sharing going on.

Yuri: Yeah, that's the idea, to share the most. We are deeply in love with that idea of the first internet—where everything was open source and everyone wanted to do their best for the community and to share the most as they can and implement the common knowledge. I mean, we are sons of that generation.

Sam: I suppose I should ask about the Outsiders collaboration while we're talking. What’s going on there?

Yuri: As Andrea said before, we started to make clothes and to become a proper brand because of stores like Outsiders. Outsiders was one of the shops that made us consider that we could become a proper brand, so we wanted to celebrate that.

So we’ve gathered some elements from the outdoor world that we love and put together a few garments, just for the sake of loving the outdoors. We did a long sleeve shirt made in recycled polyester that’s overprinted, and it's essentially a t-shirt that you can wear at the club, at the office or in the mountains.

And then there’s a head gaiter for if you want to cover your neck while you bike or you run along with a bandana and a few patches. It was very spontaneous.

Sam: That comes across with what you do. Even though there’s a lot of thought behind what you make, nothing seems forced. Where do you see things going for Rayon Vert? What’s next?

Andrea: Well, right now we are working on the second iteration of our Lizard backpack. We’re taking the idea of the first backpack, which was very radical for its time, and we’re adding in details that we’ve found useful in the last few years—so it’s kind of a contemporary take on the original design.

And along with that—we’re really into this cultural stuff, the stuff that’s not just a product—whether that’s events or hikes. These simple things help us get in touch with people who share the same values as us. It helps us create a bigger picture around the product.

Sam: Yeah definitely. I better round this up now… what’s the most important thing to take on a big hike?

Andrea: Invest in a good sleeping pad because you need to sleep well.

Sam: Good answer.

Thanks to Yuri & Andrea for the answers and to Sam Waller for the questions.

Photos by Sam Waller, Andrea Casagrande, Yuri Kaban & Sofia Blu Cremaschi.

Keep up to date on Rayon Vert's antics here on their website:

RAYONVERT.INTERNATIONAL

And on Instagram: