Some names are just ready-made for adventure. Ernest Shackleton… Robert Falcon Scott… Reinhold Messner… these bold names are seemingly purpose-built for exploration and National Geographic articles.

Rick Ridgeway is no exception—sounding like a character ripped straight out of an old comic book, it’s maybe no surprise that this guy’s face is firmly carved into the Mount Rushmore of both outdoor action and activism.

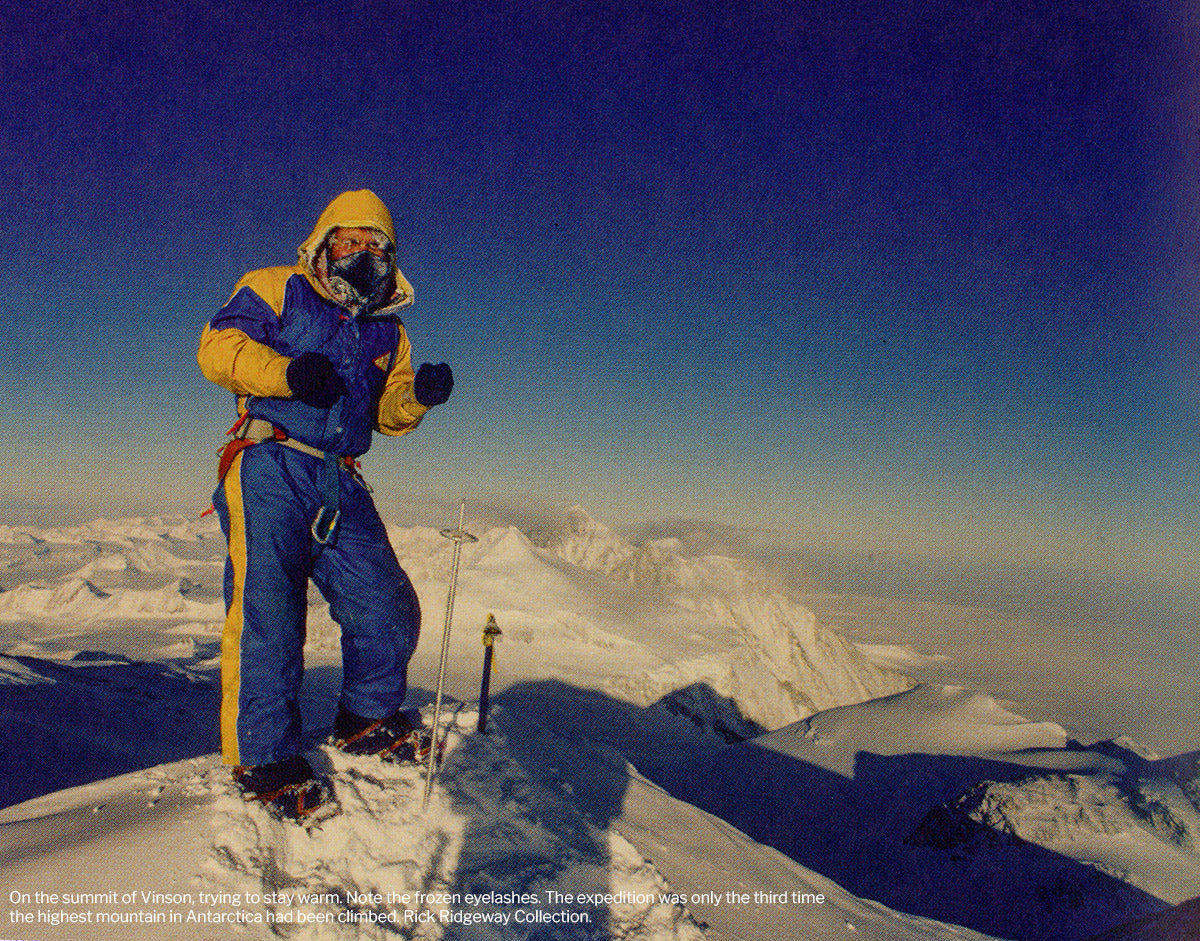

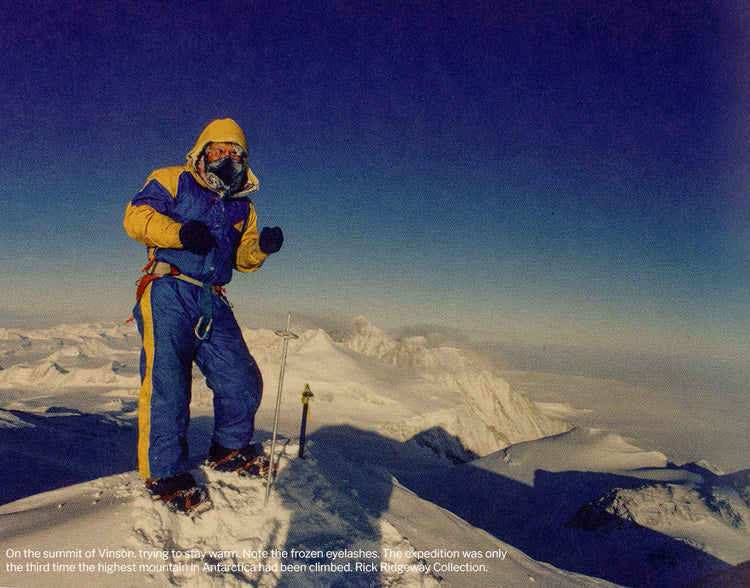

This is the mountaineer Rolling Stone once called ‘the real Indiana Jones’, a key part of the first American ascent of K2 (without an oxygen tank in sight) and the man behind the classic ‘Don’t Buy This Jacket’ anti-advert for Patagonia.

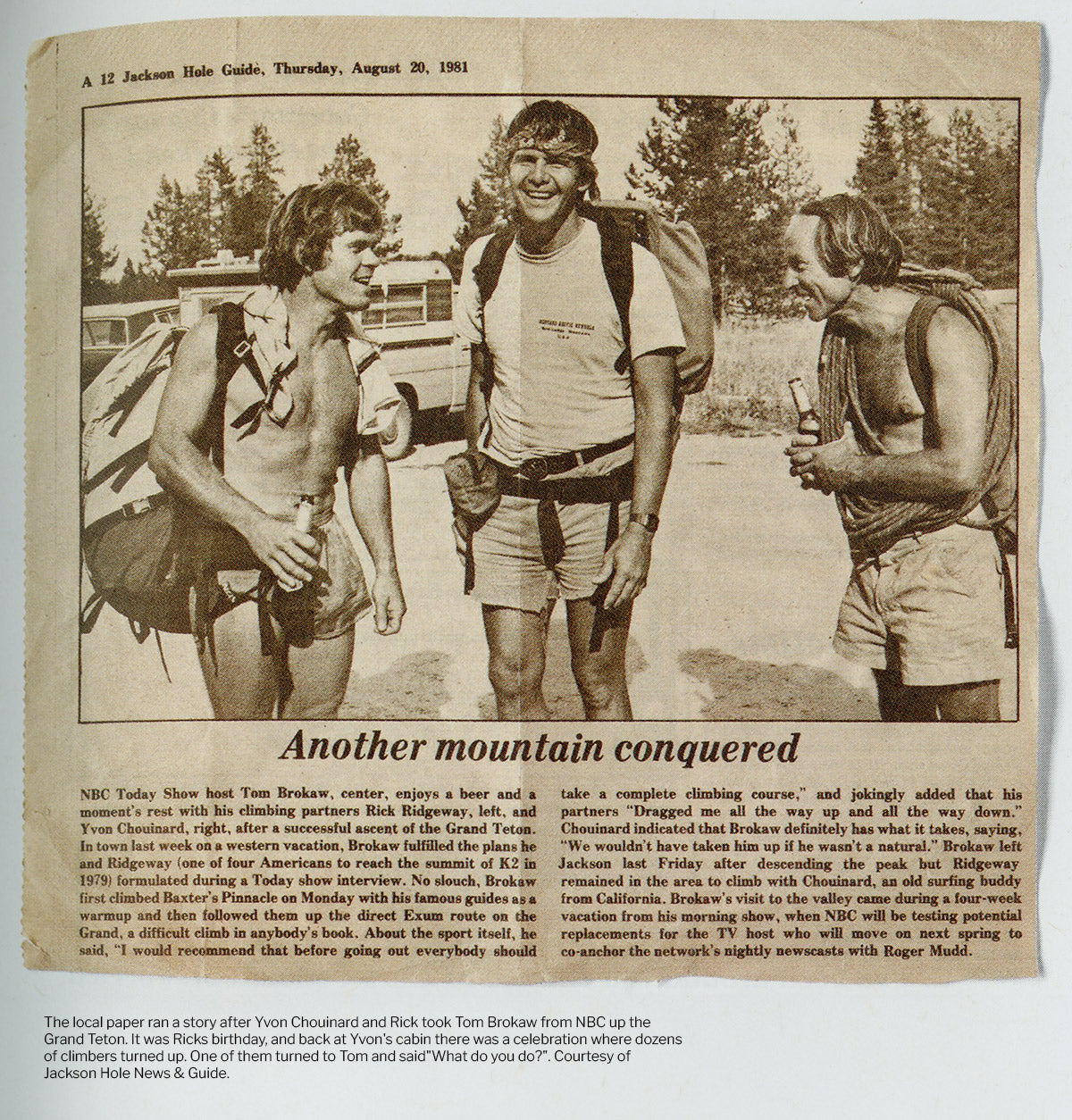

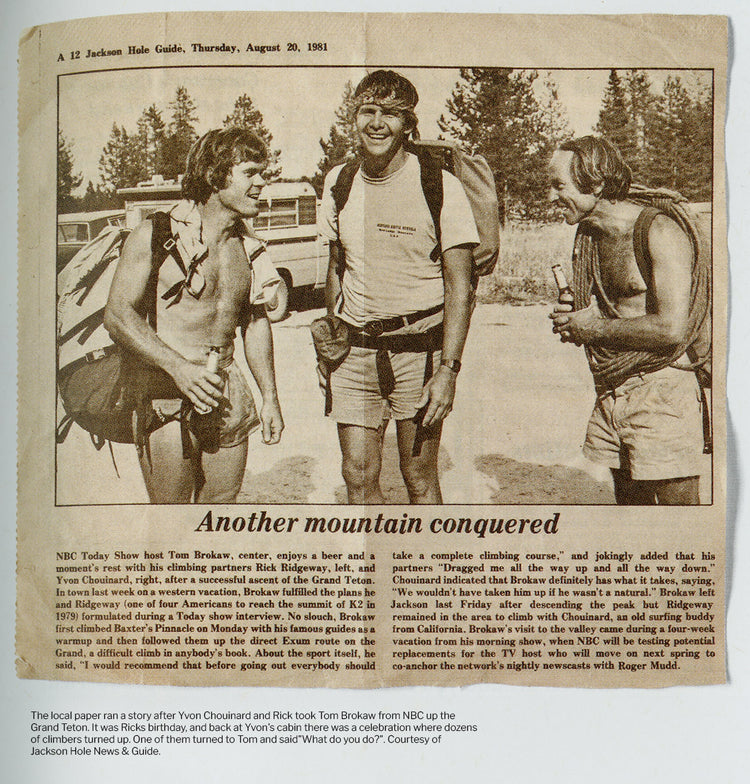

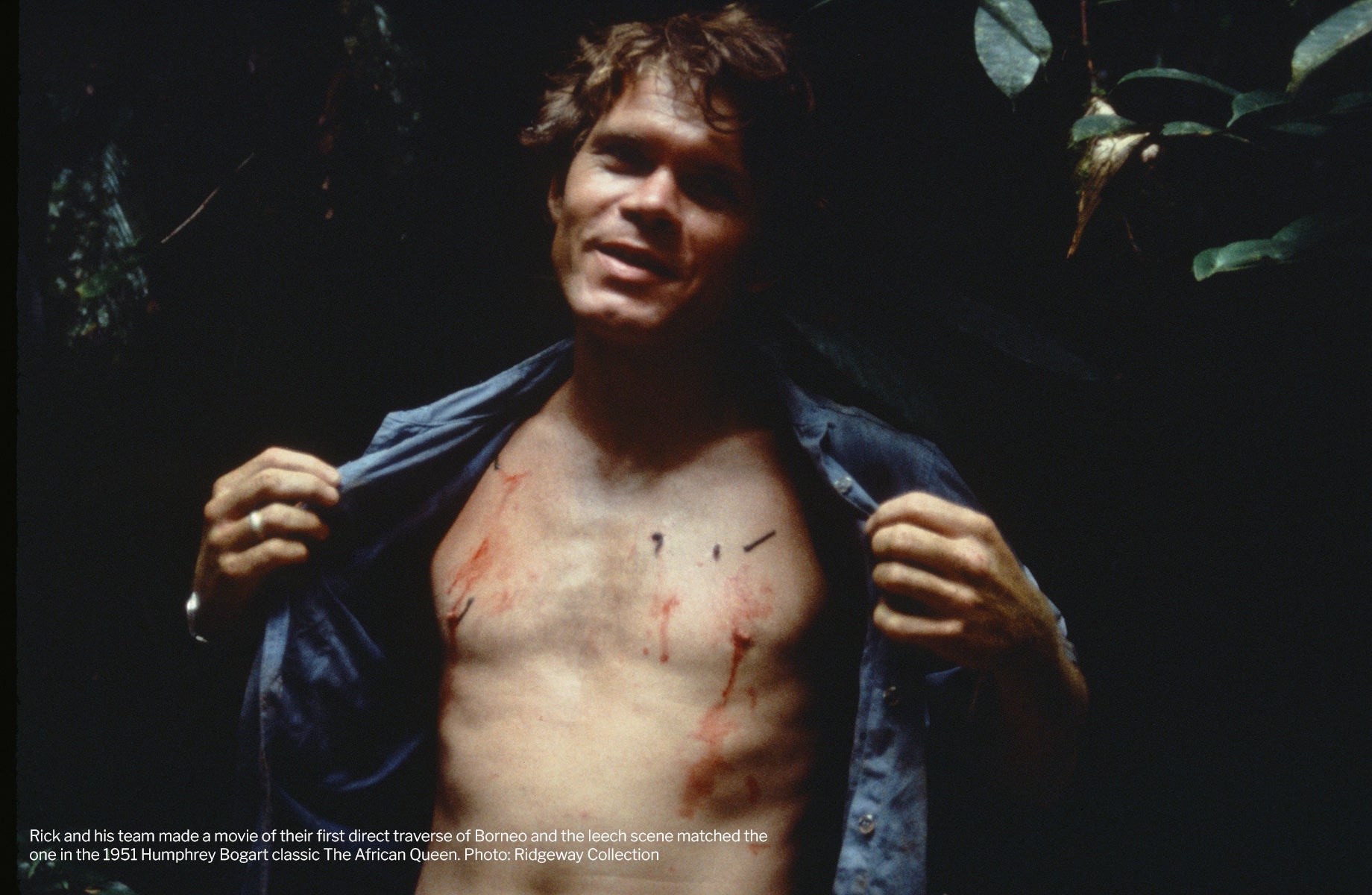

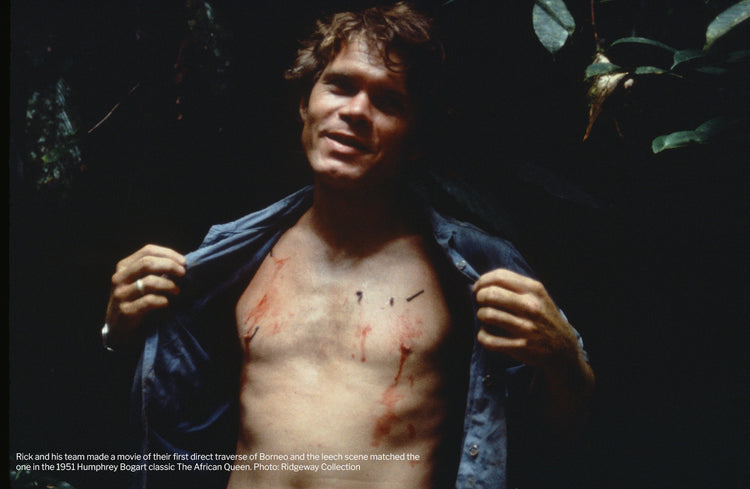

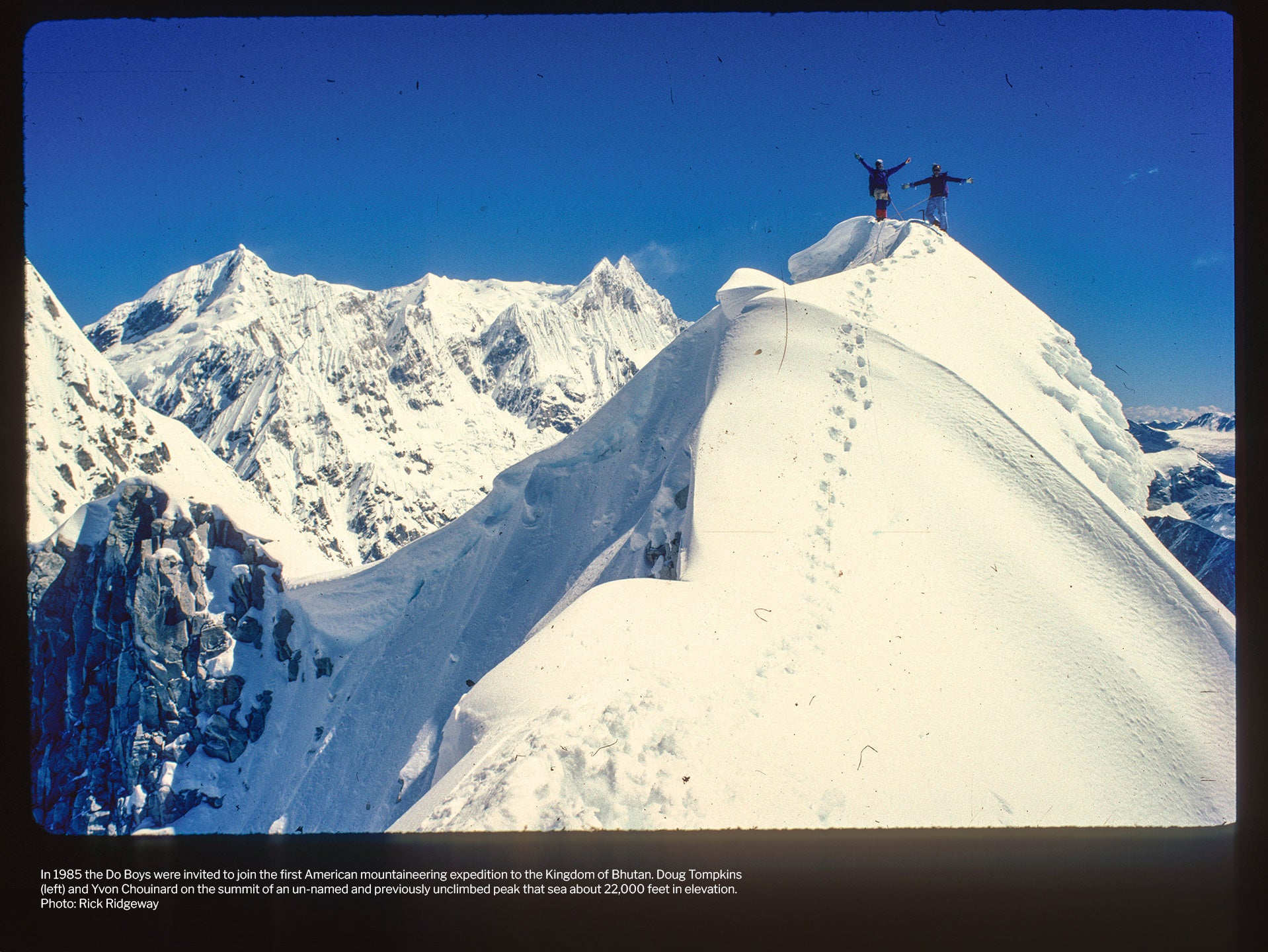

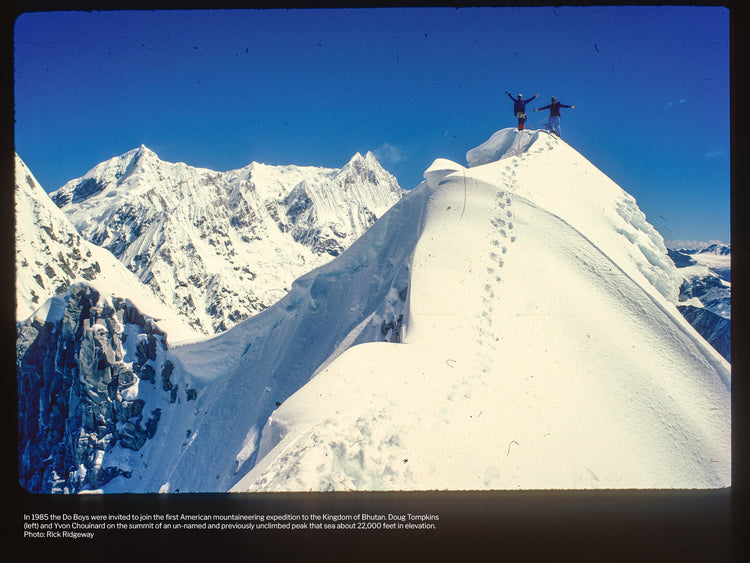

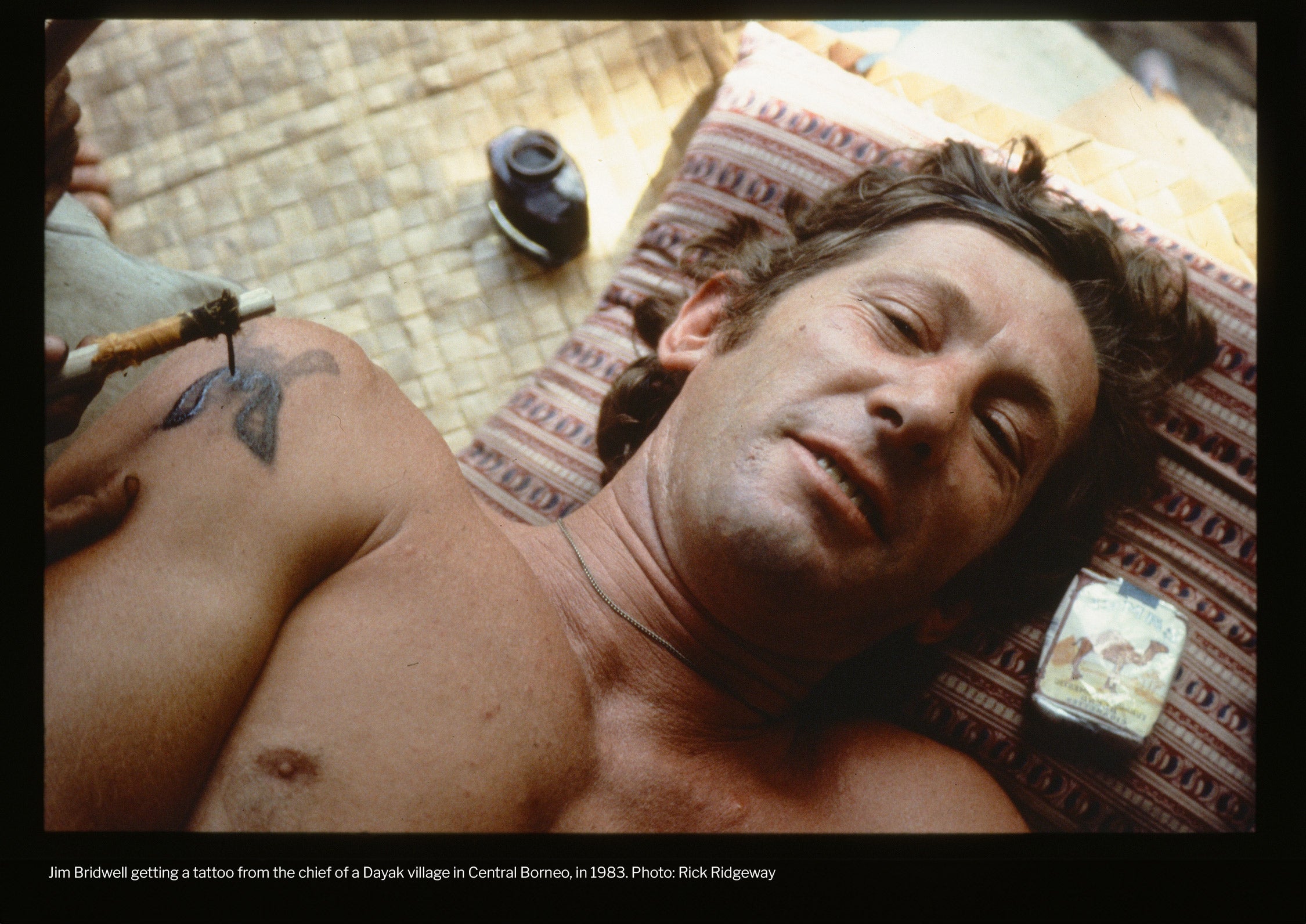

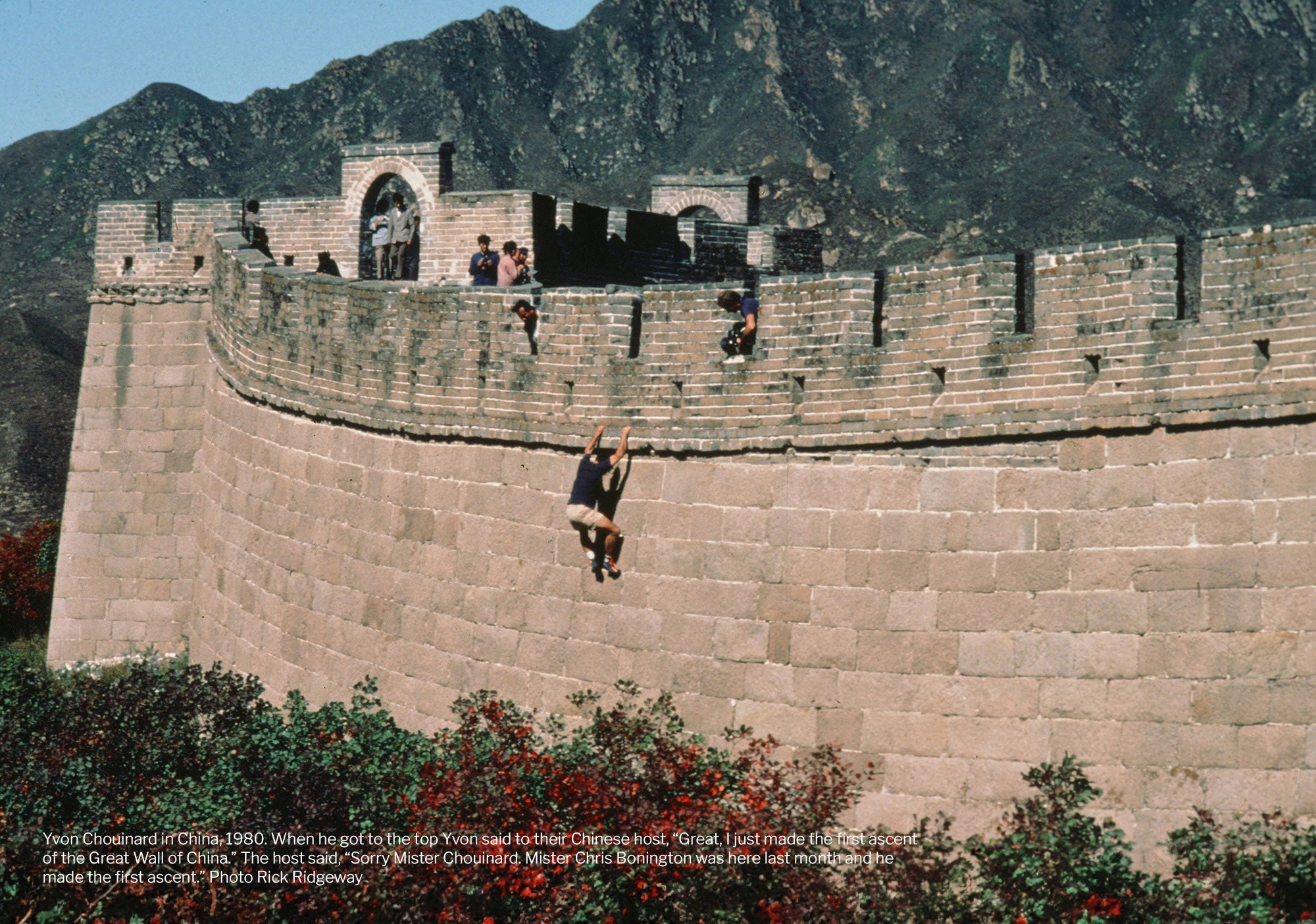

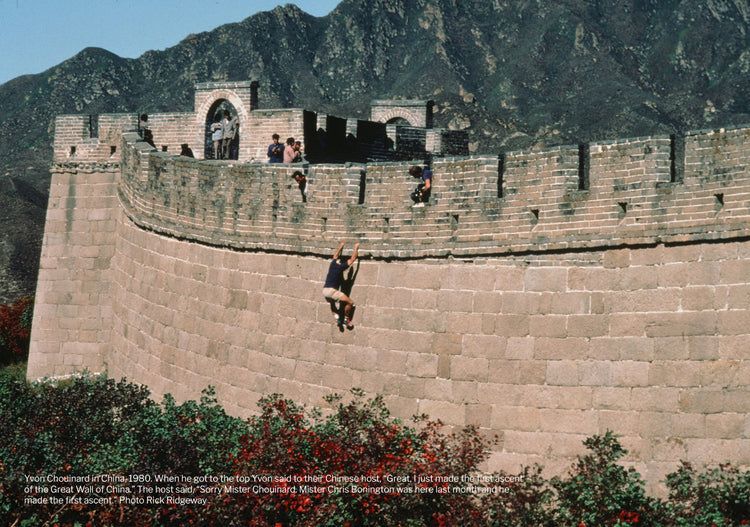

He’s a climber, surfer, sailor, conservationist, writer, family-man, film-maker, photographer, and public speaker—the inspiration behind the Swoosh’s first foray into the mountains and one of the infamous ‘Do Boys’ alongside Yvon Chouinard, Tom Brokaw and Doug Tompkins.

And now, finally—here’s what might just rank as his greatest achievement so far—an interview on the Outsiders blog…

Sam: What are you up to now? Are you ‘retired’? Are you the kind of person who can ‘retire’?

Rick: I’ve pretty much retired—although I don’t really use that word. The root of that word ‘retire’ also means withdraw, and to me, the whole idea of withdrawing from life as I’ve led it has no appeal whatsoever. I spend an average day writing in the mornings—I’ve always loved to write, it’s been a lifelong passion, and I’m still doing it. Then in the late morning I do work with the non-profits that I volunteer with—I’m on the board of several conservation groups. I have a side-business as a speaker and a business consultant, so I spend a bit of time with that. And then I’ll have Zoom calls.

I find increasingly young people reach out to me for guidance, and it’s a privilege to be able to help them and be a mentor to younger people—I always try to follow up with anybody who reaches out to me. So when I add all those things together I think I’m working more now than I was when I worked.

Sam: Yeah—that sounds like more work than I do. Are you one of those people who always needs to be busy?

Rick: I am! I stay in shape. My balance is a little off so I’m not surfing much these days, but I still run—so I run every day and that keeps me in shape. I love to hike too. So I’m still fit and fully engaged in everything.

Sam: I imagine when you started getting into climbing and mountaineering you probably didn’t think you’d go on for so long. It seems like now people just keep going.

Rick: I don’t think I ever had a time when I imagined myself as such an old duffer that I couldn’t be active… although that’s probably on the cards for all of us at some point. But I do feel privileged that I do feel active—it’s kind of cool that I can get out and run everyday.

When I joined Patagonia, Yvon encouraged me to go with him to the yoga classes that the company had at noon, and I did—I started practising yoga with him and I stuck with it. I still do yoga just about everyday—and I think that has made a difference.

Sam: I’ve talked to a few people who say that—there does seem to be correlation. You were saying before about how you’re now a bit of a mentor to people—but who did you look up to when you started? Who were your inspirations back when you first got into climbing?

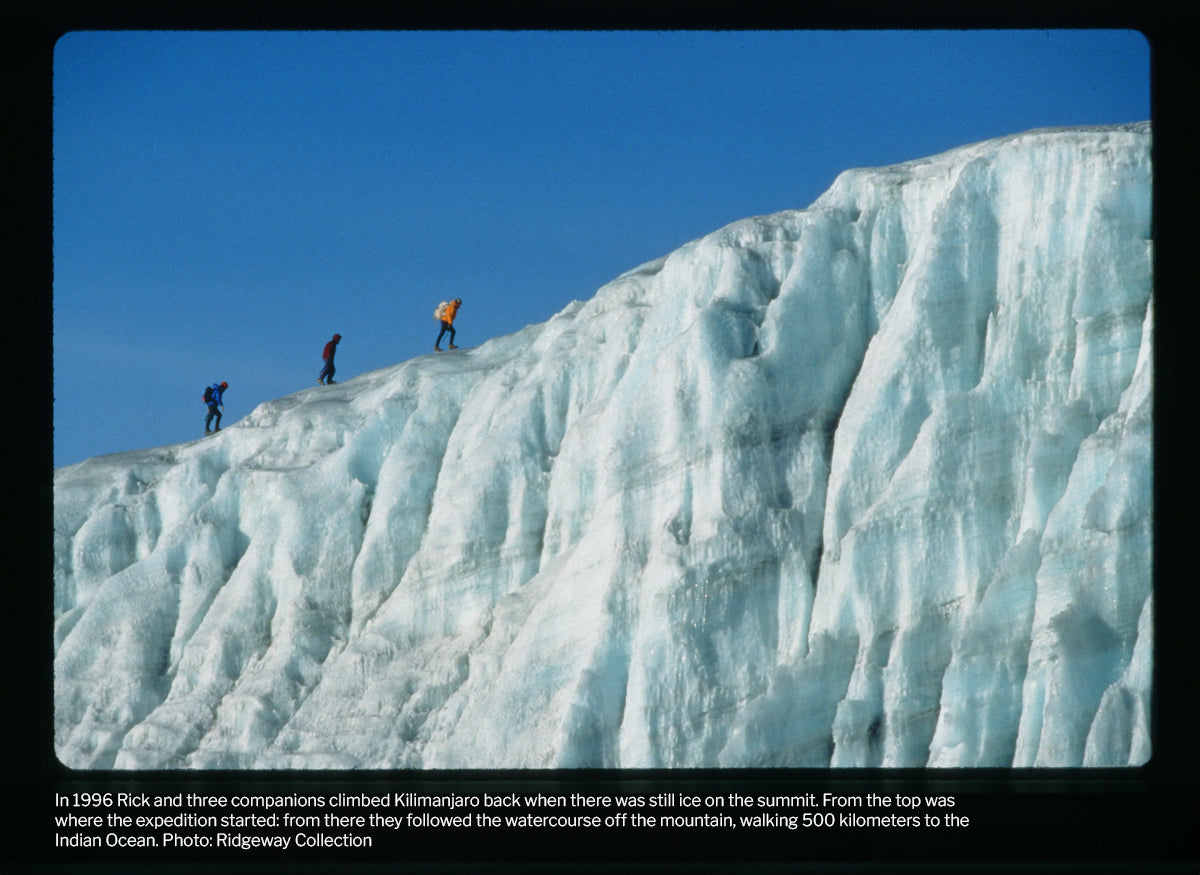

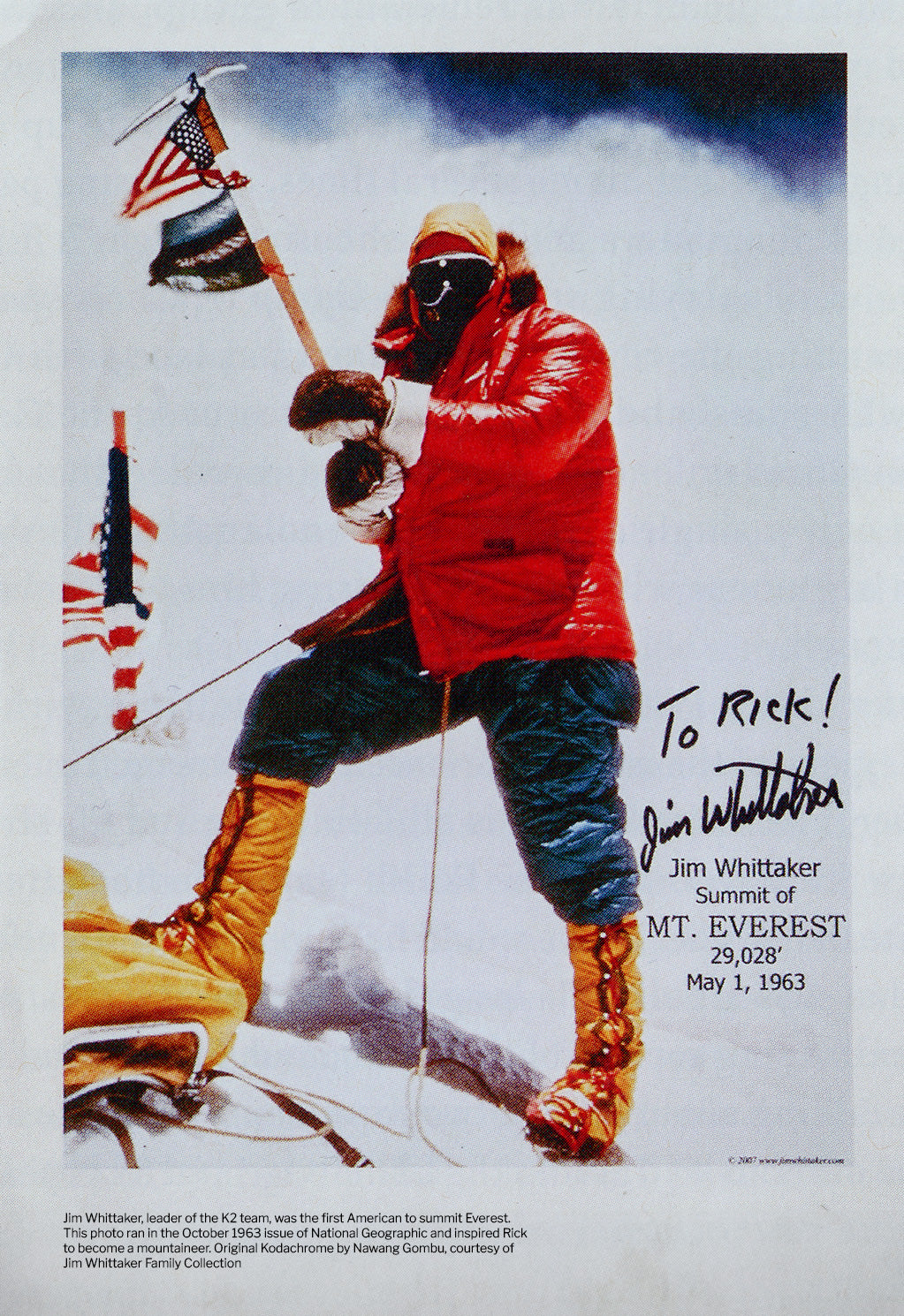

Rick: One of my first inspirations was in the early 60s, when I saw a National Geographic article about the first Americans to climb Mount Everest, and there was this picture of Jim Whittaker standing on the summit. I just said, “I want to be that guy.” I did everything I could to learn mountaineering, but my big break came when I was in my early 20s and I got myself down to Peru. I knew that that would be the place where I could really get into the big leagues—I felt like the Andes and the Himalayas were the two lodestones.

I went to a hotel in the Cordillera Blanca where I heard the climbers were hanging out. It was this fancy hotel called The Monterrey that wealthy Peruvians frequented, but the owner, this guy named Carlos Valasquez was this mischievous, fun-loving Peruvian rich guy, and he really loved climbers. He was amused by us, so he converted the changing room at the hot springs into a dormitory with bunk beds and he rented them out to climbers for 50 cents a day. So the hotel had all these rich people staying in it, and all these dirt bags, and nobody in between. I met a couple of climbers there in the dormitory, and they said that there was another climber out on a climb named Ron Fear, and when he got back he wanted to do some more peaks, and would be looking for guys to hook up with who could team together.

So when Ron showed up they introduced me, and he became my mentor. He took me under his wing. He was this crazy looking guy—he had a big black beard, he was tall and skinny and he wore bright, bright clothes. He looked like a circus clown, with red and yellow and green—the most colourful stuff you could imagine. I remember he had this backpack which had this big heart embroidered on it. And inside it said, “to Ronny, love Jan.” His girlfriend had made his pack—and she went on to start this little company called Jansport…

Sam: Haha—no way.

He was just this great character. He had this peak above the town of Huaraz called Churup that he wanted to climb by a new route. There was this big face on it which faced the town—it was the most prominent mountain you could see in the town, and it had what looked like a vertical rock band at the bottom of the face. I was thinking, “Oh my god.” I didn’t know anything, but I said, “Okay, whatever.” He took me along and we got to the top, but it was not easy. What a trial by fire!

I remember getting to the summit at about nine or ten at night, so wiped out with no bivouac gear, and trying to find our way down in partial moonlight, and finally having to bivouac. We’d taken another route down a ridge-line not knowing exactly where we were going—and I had this really primitive gear. My pants must have been made out of cotton—I just remember huddling down shivering like crazy—and then when I finally had to stand up, sheets of ice broke off my legs. But we made it down, and that was my first big climb.

Sam: I suppose you can’t really show fear when you’re young and you’re trying to prove yourself.

Rick: Yeah, and I did. He became my mentor, and I always really appreciated that. We went on to do several climbs in the Peruvian Andes, and then he introduced me to one of his mentors, an old climber named Ad Carter who was a fixture in the American Alpine Club. He organised expeditions everywhere—all over the world—and so he took me under his wing. Ad was from the previous generation—he was close with Eric Shipton, and he was with Bill Tilman on the first ascent of Nanda Devi—the highest mountain climbed by human beings back then.

So here I was with this mythical climber, who had decided that he wanted to help me out—and we went on this expedition to Peru, making a new route on one of the major mountains in the Peruvian Andes—not with him, but he was the expedition manager—he was in his 60s or 70s even then. And that was enough to get the attention of another one of Ron’s friends who became my climbing partner, this guy named Chris Chandler. So you see, it just kind of branched out.

Sam: Yeah—one thing leads to another.

Two years later Chris got invited on what then was only the second American expedition to Mount Everest—and he got me on that climb. I didn’t get to the top, but I still did a lot of the leading. And back then we were the only expedition on Everest, and you had to put the route in yourself. Chris and I put the route through the icefall and up through the Cwm, and I led a lot of the Lhotse face, but then I got sick, so I missed the summit.

But that was enough to get me on peoples’ radars so that two years later I got invited to go on what was then the first American ascent of K2—and only the third ascent. And the leader of that trip was Jim Whittaker… the guy who I’d seen in the magazine when I was 14 years old. I was 28 at the time—and when I was 14 I never could have dreamed that a little over ten years later I’d be on the second highest mountain in the world with the boyhood hero who inspired me to go on that path in the first place.

So just to get back to your original question, when I think back to the people who took me under their wings and inspired and guided me, it’s incumbent on me to do the same for younger people. Like I said, it’s not a burden, it’s a privilege.

Sam: Quite often when you read about the different generations of climbing, they’re usually talked about as really clean cut things—like “this generation came and completely changed things.” Was that really the case, or was it much vaguer?

Rick: Yeah—I think that we organise any given time into a category and give it a label when we’re at a point when we’re looking back on it. At the time you seldom appreciate that you’re in something that someday is going to be called ‘the golden age’. It was just what everybody was doing—or at least everybody who was part of the tribe that I wanted to belong to. And that’s how I felt about it—the climbers in the 60s and 70s were dirtbags.

I can’t remember his name, but there was one climber in Yosemite who was a philosophical thinker, and I remember he said about climbers, “At both ends of the social spectrum, there lies a leisure class.” And that’s how I felt about us. We dismissed the idea of a career—we all worked hard at our sport, and to make money so we could pursue our sport, but it was always climbing that came first. And we never would have thought about work in pursuit of a career—that was kind of an anathema. And those were my people—that was my tribe. We never saw ourselves as living in some golden age at the time.

Sam: How were you living back then? What were you eating? How were you scraping by?

Rick: Well, I did several things. I had a parallel passion for sailing—adventure sailing and climbing were my twin passions. So in my 20s I got a job in the crew on a rich guy’s sailboat—so I got income from that for half the year. I lived on boats most of the time, and I got good at fixing them—so I worked in boat yards. And then from an older boat repair man I learned how to be a good painter—so I got jobs painting houses and boats.

I remember one time I replied to an ad with a buddy of mine for a job at a painting company in Hawaii—but we found out that you had to be in the union, so my buddy and I hatched this plan—and when we went to the job and they asked for our union card, we said, “Well, we were working for the military in Vietnam, and we were in the union there, but the Viet Cong had attacked the office—and they’d blown up all the papers.” They bought the whole thing, so I worked in Honolulu for a while. And then back in California I was always painting people’s houses.

I was a surfer also, so I lived on the beach in this little shack with a bunch of other surfers. We’d get these jobs painting houses in Malibu for movie stars. Just the other day I was reading an interview with David Mamet in the New York Times, and he said that one of his heroes was a woman Adela Rogers St Johns—an influential writer and a movie star back in the 20s and 30s, and I thought, “Oh, I knew Adela! I used to paint her house!” But I only worked enough to fund my next climb—and all my buddies were the same.

Sam: It seems like living was pretty cheap back then—at least in California.

Rick: Oh god yeah—you could figure out how to live pretty well for next to nothing. My buddies and I were always having rich people invite us over for dinner. It was crazy—these movie stars seemed to take a liking to us. I remember my surfer buddy—his parents lived in the ritziest part of Malibu, right on the beach—and they had this apartment above their garage. So I went to my buddies’ father one day and asked if I could live in the apartment—and he was amused that I was this surfer/climber/sailor, so he’d taken a liking to me—so he said, “Yeah, sure.” And when I asked about rent he said, “What can you afford.” I paid $150 a month. I found out later that the house next door—and this was in the early 70s—rented for $15,000 a month to Woody Allen.

Sam: I don’t want to think what that would be now.

Rick: Can you imagine? I know that the garage apartment and the house just sold last year for $32 million. So I was living really well on nothing.

Sam: Why do you think the Hollywood guys took a shine to you? Was it because you were kind of like outlaws or outsiders?

Rick: Yeah—and we had good stories to tell. I guess I earned my keep telling stories.

Sam: Not a bad deal. Going back to K2—you're living this dirtbag California lifestyle, but then you’re then going on this pretty serious expedition. What goes into gearing up for something like that?

Rick: It was an old school expedition—there were a dozen climbers, and we were prepared to be there for a long time. We knew there was a history of storms and bad weather, so we might have to wait it out—and boy, that sure turned out to be the case. I know that we were above 18,000 feet for 68 days. So we had an enormous amount of supplies—and 380 porters to carry it in. And back then you had to walk a long way to even get to the mountain—it was 110 miles each way—and only half of that was on trails, the other half was on glaciers. I think the whole thing took nearly five months—so it was kind of one of the last old school expeditions.

Sam: That’s almost like a military operation.

Rick: Yeah, it was. And you had to have somebody like Jim Whittaker who could figure out how to be an effective leader. Jim had done another attempt on K2 two years before—and the porters were always going on strike. They would wait until you got way in on the Baltoro Glacier before they would strike, because they knew they had the advantage.

So anyway when they went on strike Jim opened the box with all the cash, tells all the porters to gather, and then he stands on a rock with his fistful of cash, takes out his lighter, lights up the money and burns it. Everyone was gasping—and then through the interpreter Jim says, “That was the first fistful, here goes the next one until you guys pick up your loads and get going”. So he reaches in, pulls out another wad and starts to light it, but they go, “No no no!” grab their loads and get going. He was a good leader that way.

Sam: What’s life like at 18,000 feet when you’re at camp when you’re just waiting around? How do you keep your spirits up?

Rick: You’d be telling stories and reading books. We used to have to tear the paperbacks into pieces so you could pass the instalments around. You’d read one section, and then tear it in half and give it somebody else—and then you’d get the first part of another book from someone else.

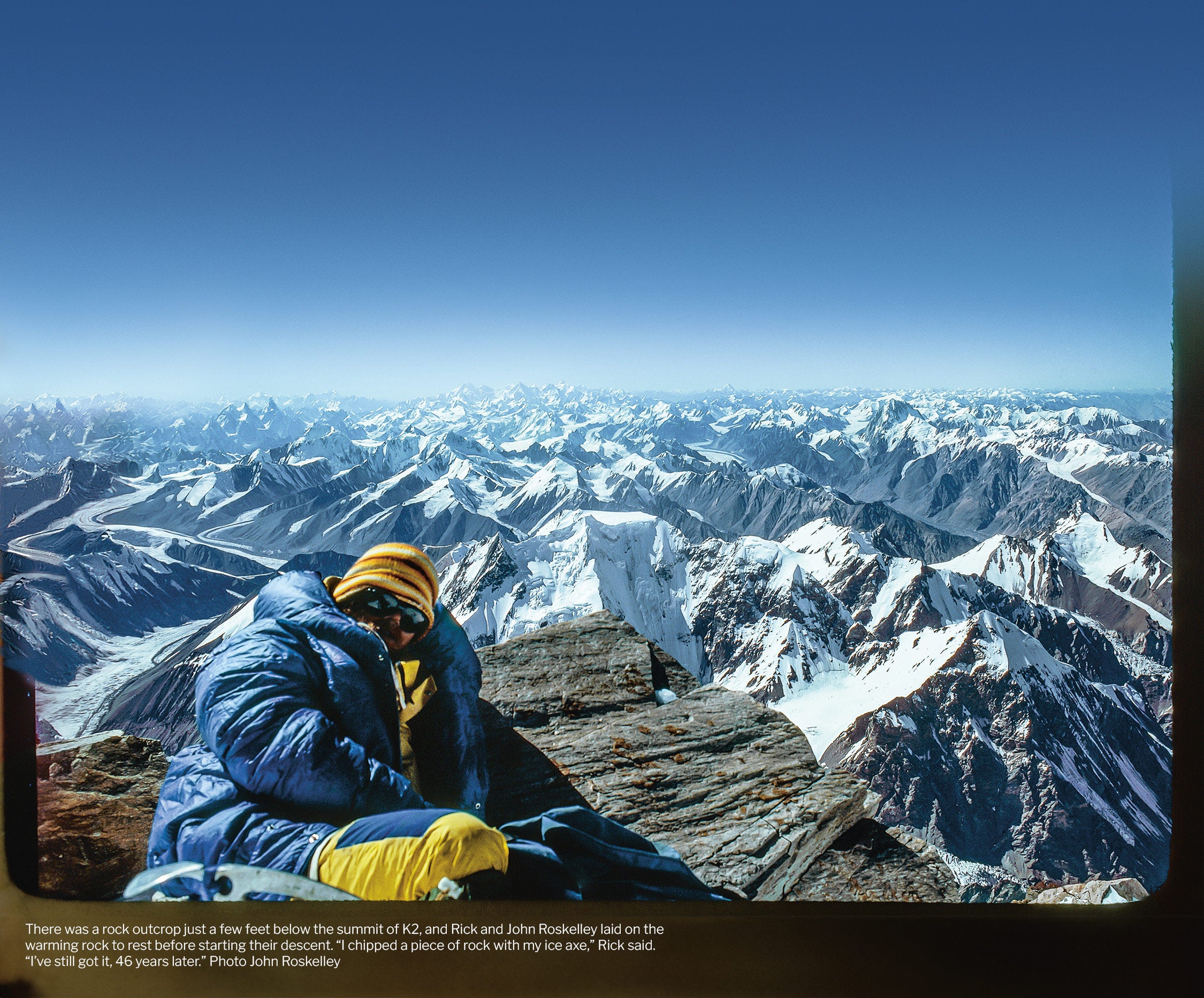

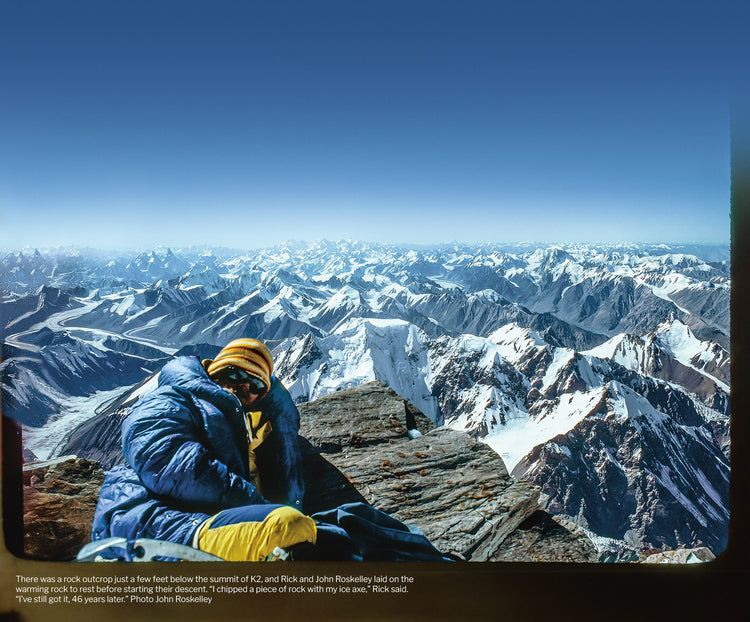

My climbing partner was John Roskelly, and I remember one day I’d just been laying there as bored as can be, and John said, “I’m sorry Rick. I apologise.” I said, “Apologise for what?” And he says, “I apologise I’m not a girl.” I said, “Yeah, you and me both!” So at least I had a tent-mate who had a great sense of humour, and that helped a lot too. But even then with that many people for that long at that high of an altitude, tempers really grew short, and we got into arguments that nearly scuttled the expedition—we barely pulled it off at the end of the day.

When I sat down to write my book about it, The Last Step, I decided that the only way to tell the story was to tell it as accurately and truthfully as I could—not to avoid the conflict, but to embrace it and even to make it the central part of the story—so that’s what I did. Going back to the very early 70s I’d had the habit of being a journalist, inspired by one of my college professors who encouraged me to keep a journal—so on the K2 climb, like on all my climbs, I kept really careful notes and wrote down the dialogue. And there were other climbers who wrote too—especially a guy named Jim Wickwire, he kept a detailed journal and he made that available to me.

I took his journal and my journal and some other notes from other members of the time, and I collated everything so that I told the story of our conflict using several different sources that all confirmed the scenes in the book. So I was confident I was accurate… but even then, it led to a lot of ill will with some of the climbers afterwards, which was hard for me, but I’ve always felt good about that decision to tell the story honestly.

Sam: Yeah—all too often you just hear about the glory—but there’s all the other stuff, from the boredom to the conflict, which kind of makes something interesting. What do you look back on from that expedition most fondly? Is it the summit, or is it something more everyday?

Rick: Well, certainly the summit of course—but at 28,000 feet without oxygen I was so wiped out and it was so hard to think clearly, so remembering the summit is kind of like remembering a dream, where there’s just an assembly of these little parts—these snippets—and I know there are parts that I don’t remember at all. I got a photograph from Jim Wickwire recently—looking down from the summit—and it brought memories of things that I’d completely forgotten about some of the details about the route, and what it was like trying to make those last steps.

But there are other things on that climb that I remember all the time. The route was on this long very sharp ridgeline, and I remember one day there was some kind of phenomenon—the only time that’s ever happened in my climbing life—where there was this sea of clouds carpeting the glacier below us, just like this fluffy carpet, and the sun was behind us, and for maybe 30 seconds or a minute the sunlight behind us cast our shadows over this sea of clouds, and I could wave my ice-axe and my arm and then my shadow was cast over this sea of clouds like I was this enormous creature from some other world. My arms were hundreds of metres long, and there was a rainbow glow around my head. And I’ve never witnessed anything like that before or since.

Another day, John and I were leading across the narrowest part of this crest—this knife edge ridge—having to traverse sideways on really steep ground. I was belaying John, and we were at 23,00 feet. It was a nice day, and I had the warm sun on my back and I was comfortable—and I was sort of semi-awake, feeding the rope out mechanically—and I saw this butterfly land right in front of me. And I didn’t really think anything of it. I just kind of looked at it—it was beautiful, this piebald butterfly—then another one landed, and it dawned on me that I was at 23,000 feet and there were two butterflies. So I yelled at John that there were a couple of butterflies around me, and he had stopped climbing and said, “They’re all around me.” There was this cloud of butterflies coming up and over the ridge—and I’ll always remember that.

I wrote about it in my book, and a few years ago an entomologist reached out to me and said he’d read the book and he was really fascinated with my anecdote—he asked if we got any photographs of the butterflies, and John did. We sent it over and he managed to identify the species—Vanessa cardui, the Painted Lady butterfly—and then wrote an article which was published in a scientific journal about it. He did some analysis and wrote about how the butterflies must have been on a migration and then were probably caught in an updraft and swept up the snow slopes. I’ve never confirmed this, but I’ve been told that we got in the Guiness Book of Records for the highest sighting of a butterfly.

Sam: That’s quite a claim to fame. I suppose both of those memories are things you’d never have imagined happening when you set off. Is that one of the appeals to these kinds of adventurers—how you’ll never know what’s going to happen?

Rick: Of course—you never know what cards you’re going to be dealt.

Sam: Around this time you were working for Kelty weren’t you—helping to design their backpacks?

Rick: I was—right through into the 80s and early 90s.. I worked for them for 21 years, helping them with field testing, product development and marketing. And when I met Yvon in the early 70s, I started working for him as a contractor, and that’s one of the ways I made my money, as well as being a photographer and a film-maker and a writer. That’s how I was making my living, and I was doing better and better at it, but back in the 70s and early 80s I didn’t put much thought into how companies that my buddies had started could become such iconic brands one day. The realisation of where they were heading was a little slow—it wasn’t like some epiphanous moment. It just happened little by little—an accretion of a lot of thinking on Yvon and Doug’s part, and thinking about the larger context for their businesses and the environmental crisis that was unfolding, and those guys became a major influence on me.

Sam: How did you manage to balance all this stuff? You were working for brands, you were going on expeditions and you had a family—how did you keep everything evened out?

Rick: The biggest part was marrying somebody who allowed me to do that. We always worked together to try and find the right balance. My wife Jennifer had two jobs, working with Yvon at Patagonia, and working as a mother of our three children, so without her support, I never could have raised a family and continued my life of adventure. By the time I married, the photography and the film-making and the work for Kelty and Patagonia was my living, so I’d managed to turn my avocation into a vocation—but even then I wouldn’t have been able to pursue that vocation without a life partner who worked so hard to make it happen for me and for my family.

Sam: Do you think having the mix helps? Some people live very much one way—maybe their 100% dirtbag climbers, or maybe they just work all the time—but you seem to have always had a mix going on.

Rick: Yeah maybe—but every individual’s situation is different, so it's hard for anyone to use my life as a template. I think one of the key parts of how I did it successfully was marrying someone who wasn’t a climber, and had much different interests in life—that turned out to be a benefit, because she didn’t want to come on the trips with me—she’d say, “I’ll just go to the last good hotel, the one that has room service.” It also gave our children a much wider perspective of interests.

Sam: Looking at some of the adventures you went on—particularly the ‘Do Boys’ expeditions—where did the ideas for those come about? Was it just a case of seeing a photo of somewhere and wanting to see if you could get there?

Rick: Yeah, that was often it. Yvon would see a picture, and we’d go, “God! Let’s go and try to climb that mountain.” Or maybe Doug would fly over some mountain in Patagonia and go, “Hey, I just saw this thing, what do you guys think?” But some of my trips were not so much happenstance, as much as me identifying something that I thought would be a good trip, and then working hard to turn it into reality—always having my ear to the wind and ear open to what might be a good idea.

For example, being in National Geographic’s headquarters one time talking to a photographer who showed me a picture that he’d taken in the Amazon on a little plane he was flying, and way in the distance you could see this needle-like peak on the horizon. Then I did the research to find out what it was—it was this rock spire in a super remote place, and I ended up putting together an expedition to go and climb to the peak.

Or meeting George Schaller, the wildlife biologist, and learning that he had been studying these animals out in Tibet called the chiru and he really needed to know where their calving grounds were, and it was such a remote place he couldn’t figure out how to get there. He wanted to discover where their calving grounds were so he could get the Chinese to protect it before the poachers got there. So that’s where the idea came to follow the animals on foot—to follow their migration.

Sam: That was where you were carrying all your gear with those little carts wasn’t it?

Rick: Yeah—the rickshaws. Those are two examples of expeditions that came from just getting a snippet of something that sounded intriguing, and then digging into it and coming up with an adventure.

Sam: Aside from that trip which seemed more specific, what was your drive with this stuff? I think you said somewhere that you were almost ‘conquistadors of the useless’—was it just a case of wanting to see what it was like in these places—to put yourself into these interesting situations?

Rick: Yeah—the climbing had an element of just tackling something inherently difficult as a challenge—there was always an appeal in that. And then there’s the appeal in getting to the wildest places on the planet, and the appeal of doing that with people who were close friends, and the camaraderie of the adventure. But that rickshaw trip was different—because that was taking the skills I learned as a mountaineer, and applying that to an effort to preserve a species which was being threatened by poachers.

Sam: There was a goal beyond having fun.

Rick: Way beyond. And it worked. We found those calving grounds and we documented them and publicised everything, and the biologists used that publicity to convince the Chinese to create a protective area. We pulled it off, and it was very fulfilling. That was a really hard trip—a challenging expedition in this wild part of the planet—so it was a kick-ass adventure, but we weren’t conquistadors of the useless any more. We used our adventure skills to accomplish something that was really not about us, but about saving these animals—and that felt so fulfilling and so different. And that’s where my inspiration to work more in conservation was really rooted.

Sam: Have you got any more of these expeditions lined up?

Rick: No—but I’m still getting out a little bit. I was in Kenya in September, and I did a walk with a buddy of mine walking 100 miles in bushland, and then I was in India in the Western Gap mountains, surveying turtles and tortoises for a conservation project. So I’m still out in the wilds, but the kind of trips that I enjoy now have some element of conservation in them.

Sam: That makes sense. I know you only had an hour to talk so I’ll wrap this up now. Final question… what is trundling?

Oh trundling? That was something we always enjoyed doing back in the day when you’d be in some remote place on a steep hillside, and there’d be a big rock that you could push loose and see it fly down the mountainside. I don’t think people trundle anymore. There are too many people to do it in the mountains now—back then we knew there was no one else around.