M&Ms, gummy sweets and cold instant noodles might sound like the contents of a student’s cupboard, but that’s actually the well-balanced diet of Josh Perry, the British hiker who fully shattered the self-supported fastest known time record on the Pacific Crest Trail last year.

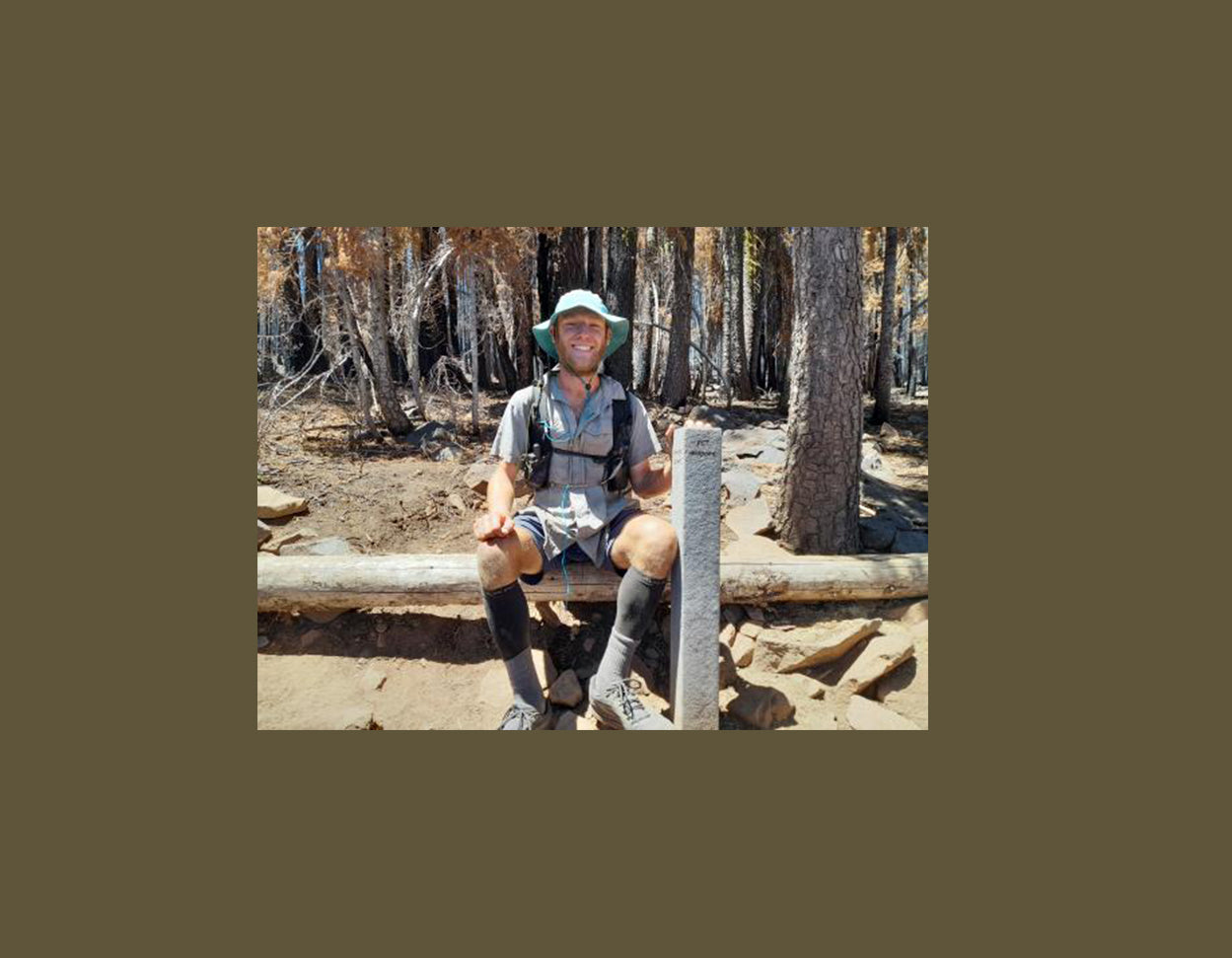

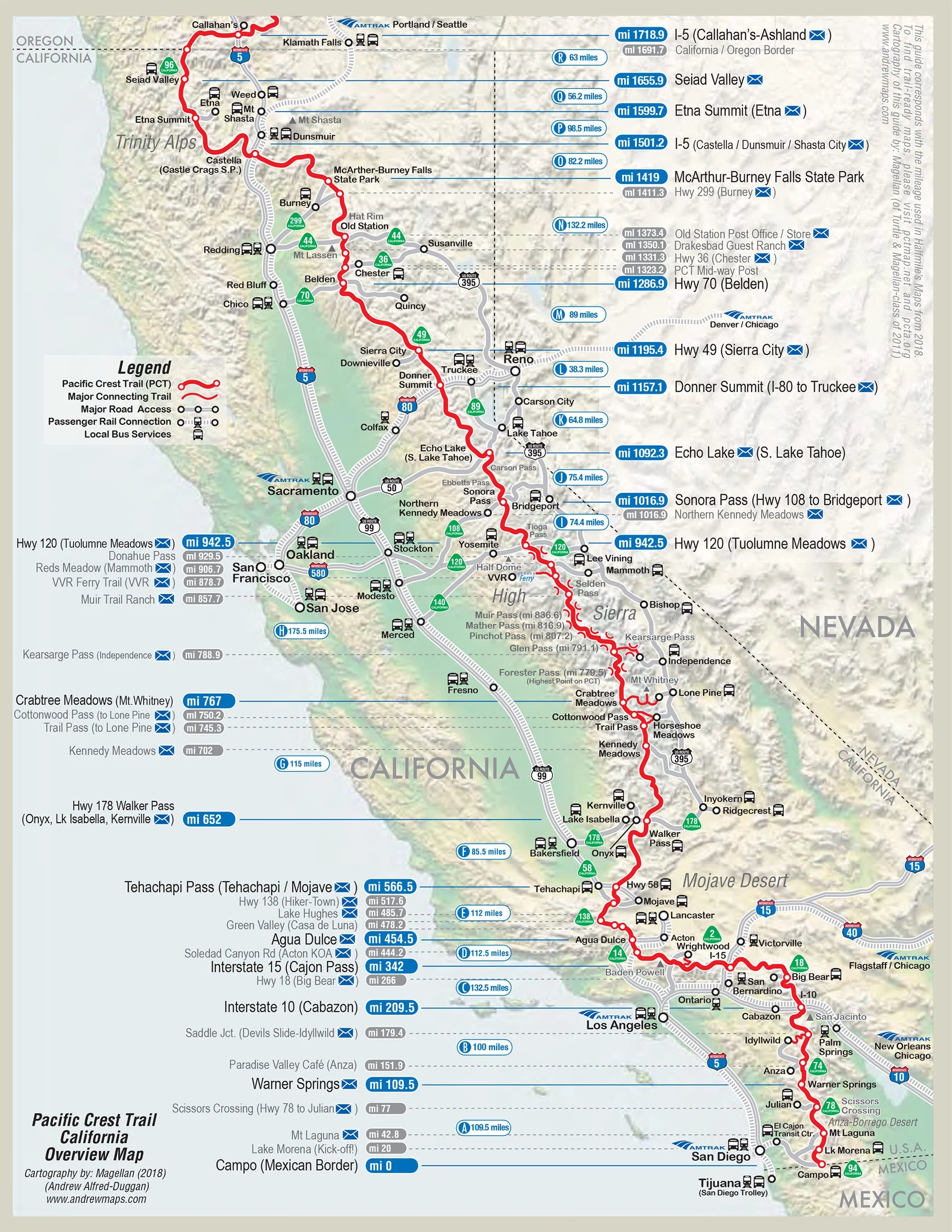

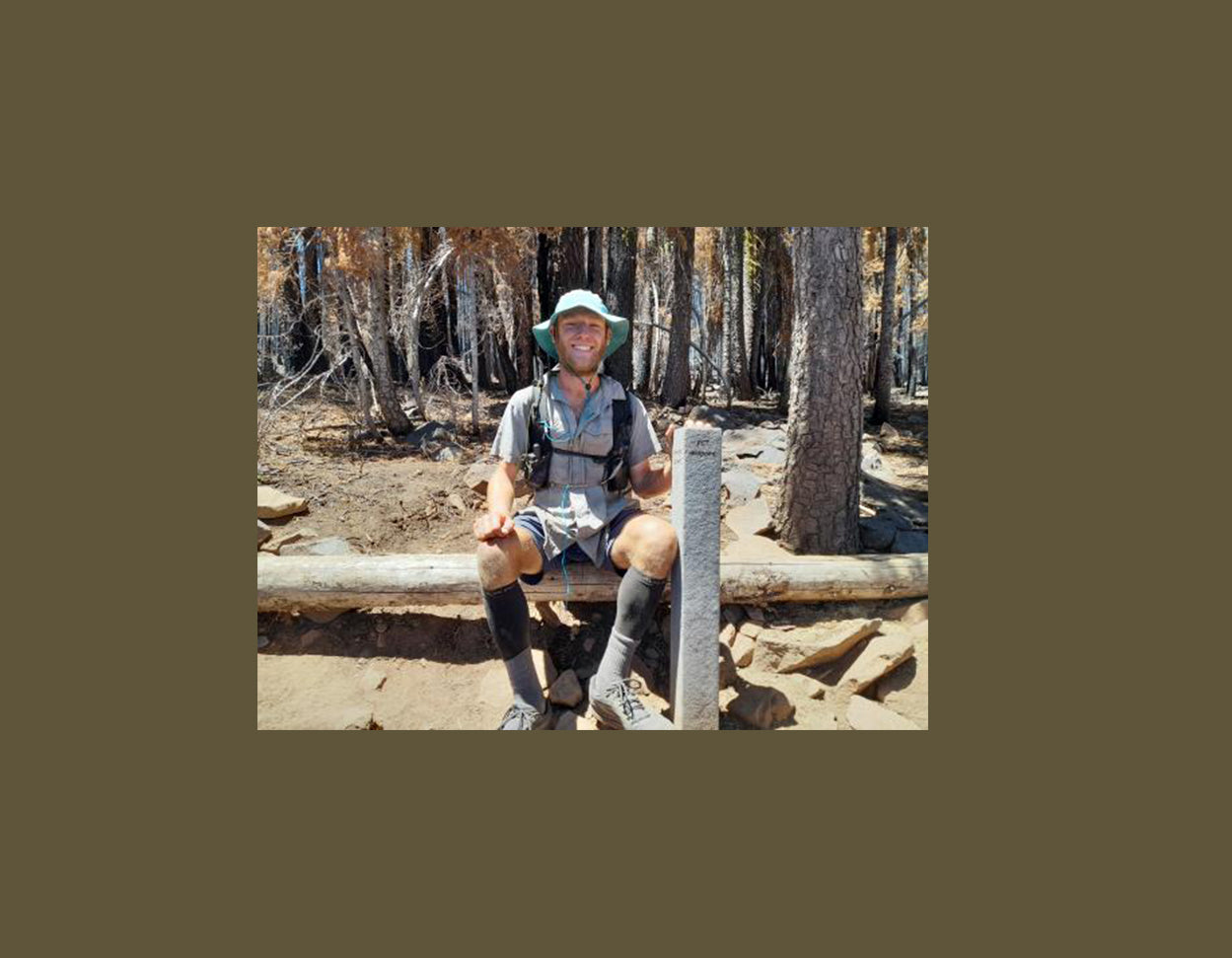

Whilst it usually takes mortals around six months to complete the 2,653 trek from the top of Mexico to the bottom of Canada, Josh ‘shuffled’ his way through some of the finest scenery the United States has to offer in a breezy 55 days, 16 hours and 54 minutes—knocking five days off the previous record… with seemingly zero avocado salads in sight.

Back home for winter, I talked to him about his record-breaking hike, his unorthodox diet and his love of ‘Type 3’ fun.

Starting at the beginning, what got you into thru-hiking in the first place?

I think I was 17. I’d moved up to Leeds and was joking around with a friend, saying, “Do you think I could walk back to Hertfordshire?” He didn’t think I could, but I said, “I’ll see you in a week.” I printed my route off Google Maps that morning and I walked it. It was about 190 miles, and it was horrific, absolutely awful.

And before that, were your family into camping or running or anything?

No. I did karate, and I’d run away from security guards whilst out skateboarding, but that was the extent of my running and exercise. I didn’t start running until I was 21, and my family didn’t exercise at all. It came from the left field.

What came after that?

A year later Heather Anderson set the PCT record, and I remember reading an article about it, with no context. I didn’t know what the Pacific Crest Trail was, but reading about it just put what I’d done in perspective, making it seem very small and insignificant. So then I decided to do the Camino de Santiago, which was my first taste of long distance stuff. That’s about 550 miles across Spain, starting on the French side of the Pyrenees, down this old religious pilgrimage.

By this point was the PCT something you were thinking about?

It was the next year when I thought I wanted to do that. I walked across Japan on the 88 Temple Pilgrimage in 2015. I was on my own, walking all day, and I realised I was doing big miles. That’s when I thought, ‘Yeah, I want to go for that record.’ I don’t think I really knew what it meant at the time, but that was when the seed was planted.

Coming to this year and your record—just so I get this right, before you set off, you had to send food out to your future self, didn’t you?

Yeah—I sent out 19 re-supply boxes beforehand. Roughly every 150 miles or so there’d be a box. I didn’t do that much of a good job of it this year as I was basically homeless when I was sending them out—hitchhiking to post offices to send them out. I’d send around 12,000 calories a day in each box, and then shoes and socks, spare underwear, hand sanitiser and sun cream—pretty much everything I could think of.

“And that gave me the confirmation I needed to know I was doing everything right by eating junk food. “

And from what I read, you just ate M&Ms the whole time. It looks like you had the diet of an eight year old.

I’d have 3,000 calories of M&Ms, 3,000 calories of candy, 3,000 calories of nuts, and 3,000 calories of bars. In the first year of lockdown I read this study in the New Scientist which said that you naturally consume a set amount of protein, no matter how many calories that is. So if you’re on a high protein diet, you consume less calories, but if you’re on a low protein diet, you need a lot more calories to get that protein. And that gave me the confirmation I needed to know I was doing everything right by eating junk food.

Would you have a hot meal at the end of the day or anything?

No. I don’t carry a stove. I did eat ramen cold in the desert, with cold water on it. And then in towns I’d try to get a hot meal and fresh fruit, just so I had some sort of nutrients. One day in a very sleep deprived state, I convinced myself that I had scurvy. I think it’d been eight days since I’d had any food that wasn’t junk food, and I was feeling awful. I was convinced I was getting scurvy for about 12 hours.

Are those kinds of moments fairly regular when you’re out there on your own? You must have constant internal arguments.

Generally I’m quite good at dealing with my head. I find the whole thing quite meditative, but you can get in a spiral and lose two or three hours to it, without even realising. And that can be really nice, as the days are really long, so anything that passes the time quickly isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

It’s very easy to distract yourself from the boredom, by focusing on where your next water is coming from, or how many miles a day you’re going to do to get to your next food supply. There are lots of small, and very essential tasks that you can hyperfocus on, to distract yourself for a while… but then you get bored of doing that. But boredom can be good, I think it’s all about understanding your mind and learning to accept your mind as it is in the moment.

Rather than wishing away time?

Yeah, it’s about being present, and learning to be comfortable with yourself. You have to get used to that out there.

I suppose there’s no escape out there. It’s not like you can just put the TV on.

You can listen to music or audiobooks, but if you don’t have the mental energy to focus on those things as you’re expending all your physical energy, you might be listening, but you’re not taking it in at all. A lot of the time you’re stuck with your thoughts, so you have to learn to accept them. You’ve got to maintain positive reinforcement, because it’s very easy to convince yourself that it’s worse than it really is. But when that’s not happening, it’s glorious. Just enjoying it all.

And all the while you’re moving at a decent speed. Is it a run, or a fast walk?

It’s the shuffle, as I call it—going about three or four miles an hour. For the first part of the trail I was taking more breaks and caring for my body more—stretching and massaging—swimming in the lakes to clean myself and cool myself off, but by about halfway, tendonitis caught up with me and I couldn’t move fast enough. Because I was moving slow, I didn’t have time to do any of that stuff, and because I didn’t have time to do that stuff, it got worse. So once the tendonitis started, all my waking hours were spent moving. One day I did 48 miles, with only eight minutes of stopping.

How much sleep are you getting in all this?

I would try to sleep for six hours a night. I slept as little as 70 minutes one night, but for 75% of the nights I’d sleep for four and a half to six hours. I try to sleep in 90 minute cycles because it’s easier to wake up. I’ve found that if I wake up in the middle of a sleep cycle I’m more likely not to wake up, whereas it’s easier to get up at the end of a 90 minute cycle.

I’ve never heard that before. How does that work?

My understanding isn’t amazing, but my takeaway from it is that you go from lighter sleep, to deep sleep, to REM sleep, then the cycle’s almost to an end. It’s at the end point where you’re at the lightest phase, so when you wake up, you feel the least groggy. People disagree with it, but the three or four of us who do this kind of stuff a lot have all come to the same rough conclusion with it.

How did it feel when you were coming to the end of your journey?

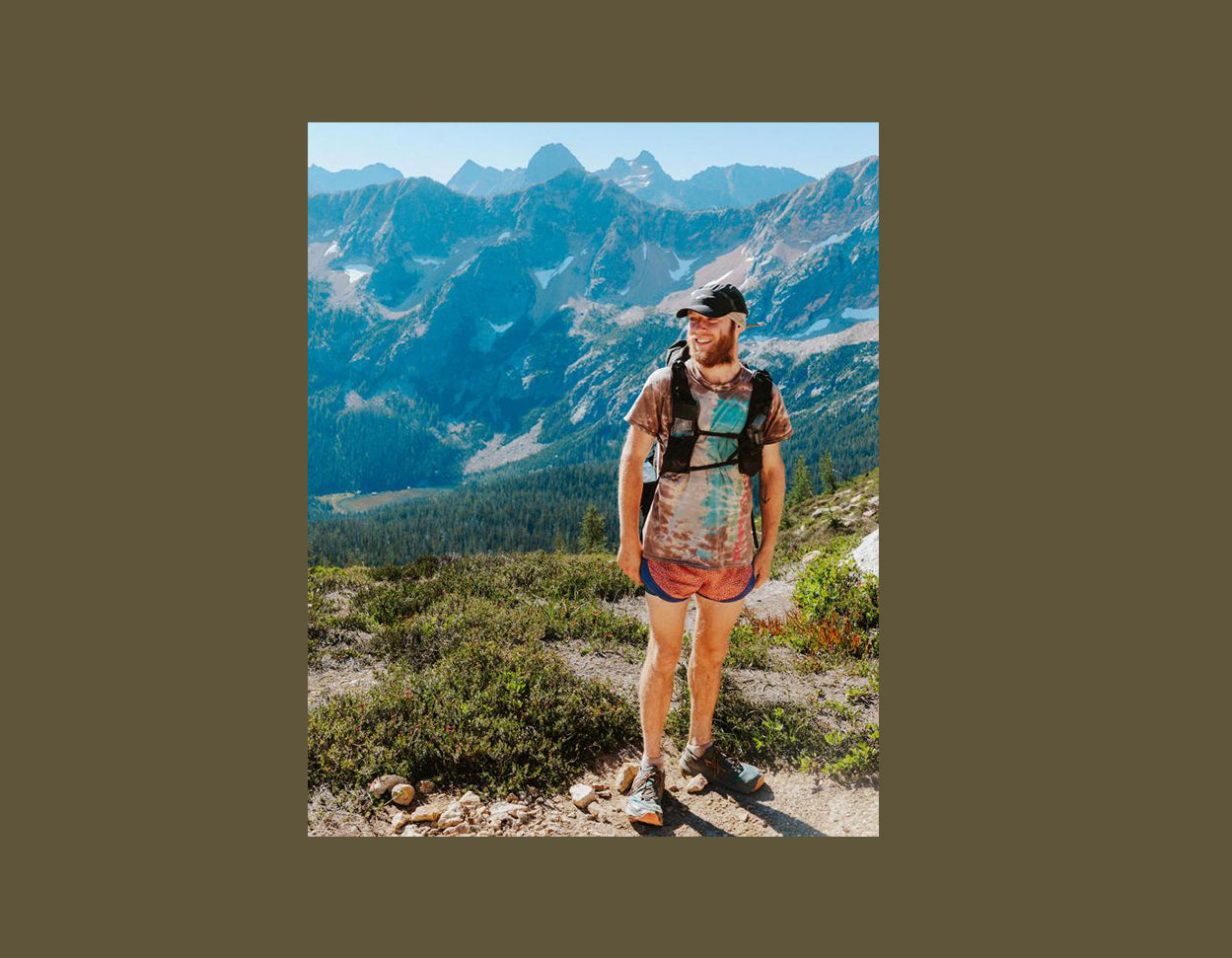

Halfway through the state of Washington, with 250 miles to go, I had what I felt like was going to be my big cathartic emotional moment, when I realised I was going to do it. It was at the spot where I actually first stepped onto the PCT five years before. I walked down this pass in my underwear and not a lot else, because my shorts didn’t fit me by that point. I had tears in my eyes and all these day-hikers were going the opposite way staring at me, thinking what the hell is this person doing? And that was the most emotional point for me.

Then the last few hundred miles almost felt like a victory lap. I’d just overcome ten days of absolute hell—I’d gone through the hard bit and just had to get through the last few days. But actually finishing was almost bittersweet. There was the relief of it being over, but there wasn’t a lot else to start with. I’d cried a lot on the trail, but I didn’t cry until fifteen hours after I’d finished.

I met someone who was telling a story about this kid he met on the Appalachian trail in 2016 who was stoked to be doing big miles, and was giving it all that about how he was going to set the PCT record. The person telling me the story was saying how some people never get there—and never do what they want to do. And then as we were talking I realised that he’d met me, six years earlier, and he was telling me about me. And by that point I was blubbering like a baby. That was the most powerful moment after I’d finished it.

When you realised how far you’d come?

Yeah, it was the moment when I realised I’d actually accomplished a goal I’d had for a decade.

That’s quite rare for people isn’t it? It’s not often that people live their dreams at that level.

No. It’s not hyperbolic to say that finding out about Heather’s PCT hike changed my life. It introduced me to thru-hiking, and I’ve hiked over 20,000 miles now. And it introduced me to running—and I’ve now run daily for years. So that’s why it feels like the culmination of a journey—I set off with this ridiculous goal eight years ago of setting the record, before I had any business thinking I could do it. And it’s very rare for people to do that.

Sometimes with arduous things like this it’s easy to talk about the bad bits—the struggles. But what’s the other side? What bits do you enjoy?

Basically all of it. The general day-to-day is so good, that it almost becomes banal or mundane how fantastic your day is, so the bad points just feel lower. Going through the Sierras for nine days, it felt like I was the strongest I’d ever been on a trail… until I thought I’d got scurvy. Each day was through the most scenic places in the US, this incredible landscape, and I was getting to move through it in a way that brings me the most joy. Just to move fast, to jog downhills and power hike… I just felt on top of the world. And I don’t feel like I’m missing anything—because I’m getting to experience it in the way I’ve set out to experience it.

And you’re going to see so much, just because of the sheer length of the trail.

Four miles an hour isn’t fast. It might be faster than most people walk, but if a car was going that speed, you wouldn’t look out the window and think you were missing anything. You can still take it in. And also, I had hiked most of the trail in 2019. There were only maybe 300 miles I hadn’t done before.

What happened with that attempt?

I found out I was allergic to wasps 1000 miles in. I went into fairly mild anaphylactic shock, I pushed through and it just got worse. I got really light headed, and had to lay down—just collapsed on the trail. Leaving Seiad Valley, I had to lie down. And then when I came to, there were some people standing around me—a doctor and a nurse—and they were like, “You need help.” And I didn’t think I could get up the next climb at that point, so they helped take me off trail.

I imagine you’ve got to know when to call it with things like this.

Yeah, but I don’t know when to call it. That time I wasn’t really with it, and they’d taken me two miles back down, and before I could really think about quitting or not, they’d put me in a car back to town. And then on the Arizona Trail I hiked 400 miles with a stress fractured shin, which has caused me permanent damage. So I wouldn’t say I know how to call it—I’m too stubborn to quit sometimes.

But then maybe that’s why you’re good at doing it in the first place? That stubbornness is probably a good thing.

That’s the balancing act—in the moment you’re essentially trying to guess if something is bad enough to cause permanent damage, and thankfully the more of us doing this, the more we can talk together. About halfway through this, when my tendonitis was bad, Joe McConaughy—who has the Appalachian Trail record—messaged me and said, “That happened to me—it doesn’t go away, but it doesn’t get any worse either.” That gave me a lot of confidence.

It seems like there are so many variables with this, what with the terrain and the weather, a lot of it seems out of your control. Is that part of the addiction?

I imagine you’re never sure how it’s going to go.None of us are happy with the end result, because the perfect run on one of these things doesn’t exist. You’re chasing a hypothetical goal and you always end up disappointed, because you feel like you could have done better. That perfect FKT [Fastest Known Time] doesn’t happen on things this long. So there’s always a part of you that wants to go again, because you want to get it perfect, very much in the knowledge that you can’t do that. So it’s more of a statement of how few things go wrong, and how prepared against the unknown you can be, versus actually trying to have it perfect.

Do you have a favourite moment or memory from the PCT?

Running down to Cajon Pass, which is only 340 miles into the trail, on day seven—it was just ecstasy. It was just this perfectly graded, really smooth trail, in an incredible setting, and the heat had finally died down for the day… It felt like everything was perfect. And they had a Del Taco there, which is a Mexican fast food joint that I’d been fantasising about all day. I’ve gone back and thought about that 40 or 50 minutes a lot—it was incredible. And there were loads of moments like that—and sometimes you really vividly recall moments because they’re so awful as well.

Is there an element of looking back fondly on that stuff too? I remember someone explaining the levels of ‘fun’ to me once. I can’t remember them exactly, but I think Type 3 was something really bad that you then look back and laugh about. Are there elements of that with this?

Yeah. Definitely. Type 1 is fun at the time, but doesn’t really have any long term achievement to it. Type 2 isn’t fun at the time, but fun to talk about later. Then Type 3 isn’t fun at the time, and not fun to talk about later as well. Some people call Type 3 fun ‘not fun’, but I prefer Type 3.

Why are you drawn to that then?

I generally think that a lot of us have very comfortable lives. Modern life is essentially all about finding a very middling level of comfort for a lot of people, and never really pushing too far past that. Doing things like this really pushes you out of that comfort zone—and forces you to experience really low lows, and then swing back up to have really ecstatic highs. You just feel a lot more, but it is artificial and controlled—you can just quit at any time—the suffering isn’t real suffering. It only exists because you’ve decided to do it.

It’s not like you’re being chased by a pack of dogs—it’s self imposed.

Yeah—there was a moment on this where I was going around a fire closure in Oregon, and it was 46 degrees celsius, and I had thirty miles with one litre of water and no shade. That was the closest I came to real suffering—getting sunstroke and getting violently ill. That was the point where I thought I was going to quit, because I felt so awful, but pushing through was the only option because my maps would only show one way to go anyway. I wasn’t in control at that point, but for most of it, you are.

Hearing about this, it all seems like a very DIY operation—it’s not like you’ve got big sponsorship deals and endless backing.

It is. I have no real sponsorships and no backing. It’s just a labour of love. I work crappy paying jobs for six months of the year to be able to do this, so I feel like with everything I’ve given up in my normal life, I have to give this stuff my absolute everything. It feels like a duty to myself to make sure I give it my all.

Is there pride in doing it this self-sufficient way?

No. There were a couple of weeks after the PCT where I was in a situation where I was only eating one meal a day, because that was all I could afford. From a spectator's perspective, I completely understand the charm of it being a self-funded solo endeavour—all the people who inspired me did it like that, and it’s great—but being involved in it, I’m like “No, give me the corporate backing!” If I could make this my lifestyle that pays, and more sustainable, I’d 100% accept it.

What happens when you finish something like this? I imagine it’s slightly strange to be back home in England after something so extreme.

For almost eight weeks, it was all that mattered, and then when you’re finished, the dichotomy of change after you finish is so stark. Suddenly you gain a whole new perspective of how trivial it is—and how essentially dumb it is. It’s just a bit of fun, but you take it so seriously in the moment. It’s absolutely meaningless, but also really meaningful to some people.It just leaves a void. It’s very binary—you’re done, you’ve finished it and your goal is complete. And that’s the case with thru-hiking in general, but it feels much more amplified in this case. I’m very much trying to find out how I can fill that void.

That seems like a common thing. People who accomplish things like this can’t then just put their feet up.

For this, with me, it was also my Triple Crown [the informal title for completing the Appalachian Trail, the PCT and the Continental Divide Trail], and is also probably going to be my last really long hike for a while, so it almost feels like it’s the end of a chapter in my life. It very much feels like a finale, and now it’s time to figure out what’s next. I think it’d be very destructive if I kept doing these hikes in such an intense manner for much longer. I’ve already done it for so long. It’s about being aware of that, and not leaning into it. The obvious thing to do would be to jump back in and think, “Right, Appalachian Trail next year!”

Maybe it’s not exactly the most sustainable thing to be doing.

Yeah. I’m still barely running or exercising, and it’s been two months.

What next then?

I’ve really gotten into Scottish winter climbing over the past few years. I could definitely see myself pursuing alpinism for a while, and then there are shorter ‘ultra-running’ goals that I could do more sustainably.

Having goals seems important to you, whereas a lot of people can be quite aimless.

It definitely helps me focus—with everything in my life. It kind of makes the path ahead seem clearer. When I have something that I can focus on, I can base all my time around it. Not in an obsessive way, but you have something to incrementally work towards. Much in the same way people want to work towards a family or a house, having that long term goal puts you in a direction for a while, and you know what steps you need to take to get that goal.

I am curious about putting that energy into non-physical goals, and seeing how that works for me. Maybe get off bad-paying minimum wage jobs for a while… but I like to spend my energy in the mountains at the moment.

Haha fair enough. Last question… M&Ms aside, what was the best meal you ate during your long-distance shuffle?

There was a great pizza at Snoqualmie Pass. It was just a cheese pizza, but it was fantastic. I ate two 20 inch pizzas that day in 40 minutes. I was so happy.